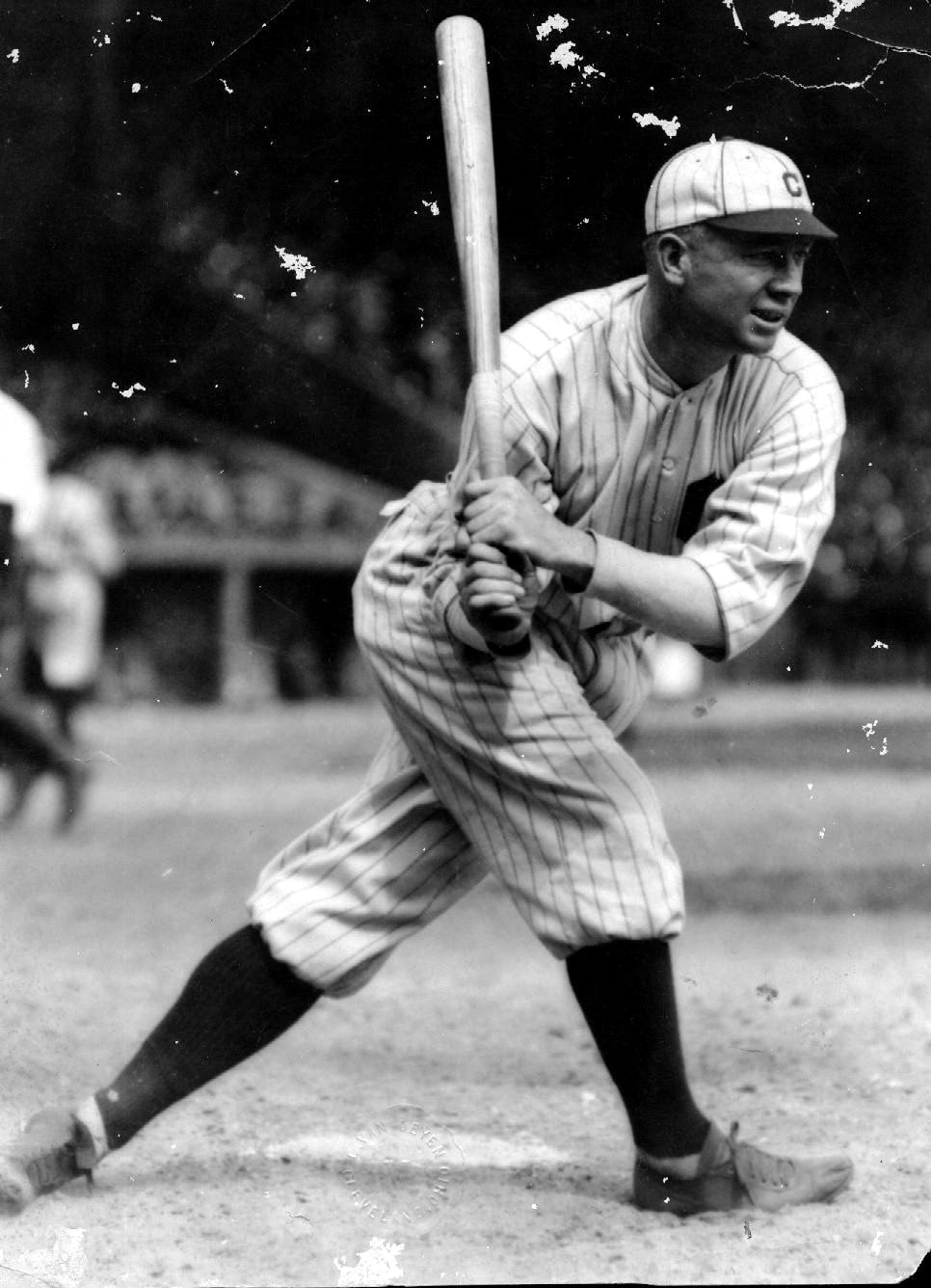

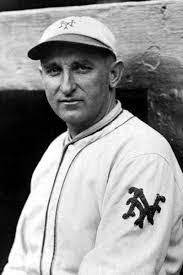

8/16/1920 - Hopefully never again! In the pre-helmet days of the sport, for the only time in the history of professional baseball, a player dies after being hit in the head by a pitch. The hit player is Cleveland Indians shortstop Ray Chapman, the pitcher responsible is New York Yankees right-handed, submarine delivery hurler, Carl "Sub" Mays. Newly married and batting .303 at the time with 97 runs scored, Chapman dies early the next morning, only 12 hours after having his temple traumatized, at the age of only twenty-nine.

Chapman

Chapman is born in Beaver Dam, Kentucky to Robert Everett Chapman and Blanche Johnson Chapman on January 15, 1891 (he will have one older brother, Roy, born in 1886, and a younger sister, Margaret, born in 1904). One of five boys the family will have, later in the same year of 1891, on November 12th, Mays is born to Methodist minister William Henry Mays and Callie Louisa Mays in Atterson, Kentucky. The two men who will forever remain locked together by the events of 8/16/1920 are born only 135 miles from each other.

Mays

Chapman moves with his family to Herrin, Illinois when he is fourteen. In Illinois, Chapman plays baseball anywhere and everywhere he can ... school, pick-up games, and semi-pro ball, playing every position except pitcher and catcher. During the 1910-1911 seasons he plays for the Springfield Senators and Davenport Prodigals squads of the Three III League, signing a contract with the Springfield when he is nineteen. In his spare time, the likeable youth also becomes a member of the United Mine Workers Union (an organization he will still be a member of at the time of his death) and puts money in his wallet mining coal. One step removed from major league baseball, in 1911, Chapman signs a contract with the minor league Toledo Mud Hens of the American Baseball Association and does well enough at that level that in August his contract is purchased by the Cleveland Napoleons (the "Forest City" franchise will also have the early nicknames of the Cleveland Lake Shores, the Cleveland Bluebirds, the Cleveland Broncos, and are known as the "Naps" during their time as the Napoleons when they are captained by Nap Lajoie, a 20-year veteran Hall-of-Famer second baseman with 3,252 hits and a lifetime batting average of .339 ... when Lajoie is traded the Philadelphia Athletics in 1914, team owner, coal magnate Charles Somers, requests the region's sportswriters give the club a new name and the wordsmiths change the name of the town's team to the Indians ... informally, the sportswriters will also call the club the Cleveland Napkins for "how well they fold"). Season already underway, in the thirty-one games Chapman gets into in 1912, the new Nap bats .312, and Cleveland, a perirenal underachieving team, wins twenty-two games and discovers it's new shortstop. Happy to have made it to the Big Show, Chapman uses his skills to become a popular player with both his teammates and local fans (along with becoming a respected opponent of other squads), and is immediately noticed for being more interested in helping the Indians win than in padding his own statistics. Three times Chapman will lead the league in sacrifices, and will set a major league record for advancing a runner with an out in 1917, accomplishing the task sixty-seven times. His team record of stealing fifty-five bases (also in 1917), will not be broken until outfielder Miguel Dilone of the Dominican Republic gets sixty-one for Cleveland in 1980. And he is no slouch on defense either, twice he will be the league leader in putouts. Coming to the plate 1,303 times, Chapman will bat a very respectable .278 for his career. Realizing what they have in Chapman, Cleveland will trade hometown favorite, shortstop Roger Peckinpaugh, to the New York Yankees (Peckinpaugh will have a seventeen year career in the majors with Cleveland, New York, Washington, where he will win a championship in 1924 and become the American League's MVP in 1925, and the Chicago White Sox).

Peckinpaugh

Bagby

Coveleski

Speaker

Looking forward to the 1920 season, the team and it's fans seem poised for their best summer ever, with a possible pennant and World Series the rewards ... the pitching staff has been solidified, the team's old manager is out, one of baseball's all-time greats, Tris Speaker, is patrolling center field, and the club has perhaps the best overall shortstop in the league leading the in-fielders ... if he decides to not retire. A seasoned veteran though still in his twenties, Chapman is the heart and soul of the team, providing high spirits on the field and when things don't go right, morale boosting in the clubhouse, often leading the team in postgame concerts that feature his rendition of the song "Dear Old Girl," delivering well timed jokes to teammates, and words of encouragement when necessary. On long road trips he keeps his companions loose with his captivating and comical story telling, and he is the player famous fans seek out when meeting with the team, with entertainment talents like Al Jolson and Will Rogers befriending him and calling him by his nickname, "Chappie." Baseball, and all that goes with it though, drop to second place in the shortstop's life when he falls in love with a Cleveland beauty named Kathleen Marie Daly, the daughter of the president of the East Ohio Gas Company. In a church filled with family and baseball friends (Tris Speaker will be Chapman's best man during the ceremony), the pair marry on October 29, 1919 and soon Chapman is contemplating retirement from the sport to give his wife his full attention, start a family (Kathleen is soon pregnant with a daughter), and begin a new career in management at a job his father-in-law is holding open for him with the gas company. Ready to pull the plug on continuing to play, he is talked into spending one more year with the Indians by Speaker, who wants to be able to count on his friend during his first year as a manager and truly believes the club can finally be baseball champions in 1920.

Happy Couple

Also trying to become champions of baseball for 1920 will be the New York Yankees and the two players and former roommates the team acquires from the Boston Red Sox ... pitcher/slugger George Herman "Babe Ruth and pitcher Carl Mays. Embarking on a much different road to the majors than that of Chapman, Mays will endure a childhood of strict religious rules that comes unwound when his minister father dies when he is twelve and his mother moves the family to Kingfisher, Oklahoma to be near Mays Family members. Father gone and transplanted to a far different state from Kentucky, the youth internalizes his grief and anger, becoming a surly loner with few friends, a persona that he brings with him to the world of baseball where he adopts a win-at-all costs attitude. Quitting high school before graduation, Mays will use the physical talents he is born with and his take-no-prisoners attitude to begin earning a living by playing on semi-pro baseball teams in Oklahoma, Kansas, and Utah. He enters the minor leagues of baseball in 1912, playing for the Boise, Idaho team of the Class D Western Tri-State League. The following year, he is off to the Class A Northwest League, playing for the league's Portland, Oregon representative. In 1914, Mays is drafted by the Triple-A International League's Providence Grays, an affiliate of the major league Detroit Tigers. Later that same year, Detroit sells Mays' contract to the Boston Red Sox. Bringing his unique "submarine" pitching style (in which the ball is released by the pitcher just above the ground, but not underhanded, with the torso bent at a right angle, and the thrower's shoulders severely rotated around an almost horizontal axis ... in Mays case, his knuckles often scrapped the dirt as he released the ball ... it is said that he learns the style from a Negro League hurler named Dizzy Dismukes, another story has the pitch coming his way courtesy of a Tacoma coach named Joe McGinnity ... no one is ever quite sure) to major league baseball in 1915, in his rookie season Mays will appear in 34 games, usually in relief, and completes the year with a mediocre 6-5 record (he is a good enough athlete also that he sometimes goes into games on his off days as a pitcher to pinch hit). Showing both the good and bad he brings to the game, and outside the lines too, Mays will often throw a not yet illegal spitball, does as much as he can get away with to the ball before putting it into play (he rubs it against the rubber on the pitching mound every time he goes out to throw), and has no problem with hitting batters that he feels are crowding the plate. Additionally, he stays to himself and doesn't participate in team activities, is quick to yell at teammates that make errors in the field when he is on the mound, talks back to his managers, and in one case, even hits a heckling fan in the stomach with a pitch he "accidently" loses control of. And as if that isn't enough to label him as a player with baggage, in his first year as a professional he begins a feud with the most notorious individual in the game, "The Georgia Peach," future Hall-of-Famer (12 time batting champion, with 4,189 hits and a .366 career batting average) Tyrus Raymond Cobb.

Mays And His Submarine StyleA veteran of ten years roaming center field and putting up astonishing batting numbers for the Detroit Tigers, early and often in his career Cobb establishes himself as someone not to be messed with ... by fellow teammates, managers, fans, and umpires, or anyone else that rubs him the wrong way (too many actual and rumored incidents to give each its proper weight, one that is witnessed by many takes place in 1912 when egged on by two teammates, and after hearing he is the result of his mother having relations with a black man, he climbs into the stands and attacks a long time New York Highlander heckler names Claude Lucker, beating the crap out of the man who has lost a hand and three fingers of his other hand in an industrial accident years before ... when he is told to stop pummeling the man by members of the crowd, he continues his assault while retorting, "I don't care if he got no feet!" ... which gets him suspended and sets in motion a strike by his teammates that causes the Tigers for one game to field a team of college recruits and sandlot players that lose to Philadelphia by a score of 24-2). Facing Mays for the first time in 1915, Cobb is instantly rubbed the wrong way when the rookie hurler throws inside on him, brushing him back from the plate. But Mays doesn't care and the two exchange words. Feud on, Mays throws at Cobb every time he comes to the plate and in the 8th inning of the game, he does it again, prompting Cobb to call the pitcher a "no good son of a bitch" as he throws his bat at the man, which causes Mays to answer in kind by declaring Cobb to be a "yellow dog." Benches emptied but the two players kept apart, when the at bat continues, the rookie throws a fastball directly at Cobb that hits the Tiger on the wrist and order needs to be restored again in a game Detroit wins 6-1 in a game in which Mays has made a statement about being a dangerous character too that is willing to go head hunting with a baseball if he thinks the situation warrants that response (later, Cobb will ask Mays point-blank if he threw at him on purpose, and the pitcher will smile and respond, "If you think so, that's all that matters.").

Spikes Up, Cobb Sliding Into St. Louis Browns

Catcher Paul Krichell

The following year, Mays appears in 44 games for the champion Red Sox, starting 24 times (18 are complete games), while posting a 18-13 record with an ERA of 2.39 (in that year's World Series, Mays will lose game three to the Brooklyn Robins, but the Boston squad will come back to repeat as champs, winning four games to one. In 1917, as the Red Sox come in second trying to defend their title, Mays wins twenty games for the first time, posting a record of 22-9 against 35 appearances on the mound and an ERA of 1.74 (he also leads the league in hitting batters, plunking hitters seventeen times, with one of the unlucky folks being Tris Speaker). In 1918, the Red Sox are pennant and World Series champions again (he will win games three and six against the Chicago Cubs, both 2-1 victories) as Mays goes 22-13 with an ERA of 2.21 (in a career highlight, he also pitches both ends of a doubleheader against the Philadelphia Athletics which clinches the pennant for Boston). At the end of the season, Mays finds someone who can put up with his grumpiness and marries Marjorie Fredricka Madden, a graduate of the New England Conservatory of Music (the couple will have two children, Carl Jr. and Elizabeth). After a short honeymoon in Missouri, Mays is then off for St. Louis where he leads a group of eighteen men in joining the U.S. Army to fight in WWI. Sworn in on 11/6, the war ends on the 11th and Mays is discharged in time for the 1919 season. A seasoned veteran and one of the game's premiere pitchers by this time, he starts the season poorly, posting a record of five wins and eleven losses ... losses he blames on the fielding behind him. Things finally come to a head when the pitcher is hit by a throw from his own catcher attempting to gun down an enemy baserunner. Upset, when Mays returns to the dugout, he just keeps going to the clubhouse where he changes out of his uniform and heads home, done with the Red Sox. Instant controversy, lots of legal posturing and finger-pointing ensues with teams jockeying for the pitcher's services (at one point the Indians will also show an interest in signing Mays) before American League president Ban Johnson finally gives in to Mays and allows him to join the roster of the New York Yankees, where he goes 9-3 to finish up the year with a record of 14-14.

Mays

Ban Johnson

A watershed year for professional baseball, as the 1920 season begins, Johnson (major league baseball is run by a commission of three people, the American League president, the National League president, and one team owner) finds himself dealing with the fallout from the Chicago White Sox losing the World Series to the Cincinnati Reds in a series that is thrown by Chicago at the behest of gamblers working for mobster Arnold Rothstein (the infamous Black Sox series in which Shoeless Joe Jackson will have his "say it ain't so, Joe" moment and eight Chicago players will eventually be banned from the game for life), the cadre of unruly players like Cobb and Mays, a host of pitching issues that find hurlers using all kinds of substances, from mud to shaving cream, to make their throws dance about the plate (the spitball will be banned beginning in 1921, with seventeen previous users of the pitch allowed to keep using it until they retire), and owners upset with $2.50 baseballs being repeatedly thrown out of games. Word out before the season begins, unless a ball has been grievously mistreated, it stays in the game.

Jackson

Rothstein

In the American League, it quickly becomes obvious that one of three teams will win the 1920 pennant ... the Chicago White Sox (winner of the previous year's pennant race), the New York Yankees (beginning their rise to dynasty level with their acquisition of Babe Ruth from the Boston Red Sox, and in a separate deal with Boston, getting the services of Mays) or the Cleveland Indians. Coming together in their twentieth year as a franchise just as Speaker had hoped they would, the 1920 version of the Indians will feature six starters batting over .300 (led by Speaker's .388) and an additional four backups also over .300, and a pitching staff that will see Jim Bagby winning 31 games, Stan Coveleski triumphing 24 (while sporting an ERA of 2.49) times, Ray Caldwell contributing 20 victories, and Duster Mails going 7-0 in nine games with a team leading ERA of 1.85. Hitting the rails in mid-August for series' with New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Washington, Cleveland goes on a 15 game swing against it's Eastern foes that sees the White Sox (72-42, .632 winning percentage), New York (72-43, .626), and the Indians (70-40, .636) all within a half game of each other. First up for the Indians will be a afternoon pitching duel between Cleveland's Coveleski (18-9) and New York's Mays (18-8), both men twenty game winners twice in previous season, scheduled to take place at 3:00 on 8/16 at New York City's Polo Grounds ("The House That Ruth Built," Yankee Stadium, will not open until April 18, 1923).

Ruth

The Polo Grounds

On Monday morning, August 16th, Chapman and a group of Indian teammates take the elevated train from their accommodations at the Ansonia Hotel on Broadway and 74th Street to Coogan's Bluff and 155th Street when the shortstop is suddenly filled by the need to sing and begins crooning in his distinctive tenor voice the words to the 1916 Robe & Rice song, "Dear Old Pal O' Mine:"

All my life is empty, since I went away

Skies don't seem to be so clear

May some angel sentry, guard you while I stray

And fate be kind to join us some sweet day

Oh, how I want you, dear old pal of mine

Each night and day I pray you're always mine

Sweetheart, may God bless you, angel hands caress you

While sweet dreams rest you, dear old pal of mine

Dearie, I'm so lonely, how I miss your smile

And your tender loving way

I just want you only, want you all the while

May God decree I have you back some day

Oh, how I want you, dear old pal of mine

Each night and day I pray you're always mine

Sweetheart, may God bless you, angel hands caress you

While sweet dreams rest you, dear old pal of mine

The Ansonia

The Polo Grounds Shuttle

A strange day about to get stranger, horribly muggy, when the Indians arrive at the Polo Grounds they find a light rain falling despite the temperature being 88 degrees and intermittent clouds that shift the day back and forth from bright and sunny to a foggy, overcast grey. Before a crowd of roughly 21,000 fans that have paid about one dollar per ticket, home plate umpire Tom Connolly (a future Hall-of-Famer that will umpire in the big leagues for over thirty years) evaluates the weather, decides the game is not in jeopardy and at just a few moments past 3:00 he shouts "Play Ball" and the game begins. With one out, in the top of the second, Cleveland scores the first run of the game on catcher Steve O'Neill's third and final homer of the season (he will bat .321 for the year), a shot into the left field bleachers (the light drizzle will stop by the end of the third inning). In the fourth, the Indians up their lead to 3-0 when third baseman Larry Gardner is walked by Mays, goes to third on a single to center by O'Neill, and scores when Yankee catcher Muddy Ruel drops a perfect throw home by Cleveland's former shortstop (it is only the normally reliable Ruel's fifth error of the year), Peckinpaugh, on a ground ball off the bat of Cleveland first baseman Doc Johnston. The Indians second score of the inning also comes from an error, this time when New York third baseman Aaron Ward butchers a ground ball (it will be Ward's thirteenth error of the season) off the bat of Cleveland second baseman loading the bases for an at bat by the pitcher, Coveleski. Supporting himself, the right handed pitcher sends a sacrifice fly out to Ping Bodie in centerfield and puts himself up by three runs. Not having much trouble with the Yankees (New York has a scoring opportunity in their portion of the second inning, but the Indian pitcher is able to work his way out of one Yankee managing to get into scoring position), Coveleski has "three up and three down" retirements of New York in the first, second, fourth, sixth, and eighth innings.

Opening the fifth inning for the Indians at the plate is Chapman. Sauntering to the batter's box swinging two bats to get loose, the Indian shortstop is batting .303, on 132 hits (27 are doubles), has scored 97 times and knocked in 49 runs. Adjusting his cap slightly, taking his spot in the batter's box, Chapman sets up crowding the plate. Starting his pitching motion, Mays sees Chapman twitch slightly and decides that the shortstop is probably bunting and makes an adjustment away from the low and outside pitch location he was going to throw into a submarine fastball up and in ... and the split-second change is enough for the throw to get away from Mays. Dirty ball lost in the between of light and grey and due to Mays pitching motion, Chapman never moves as the throw, a rising fastball, hits the helmetless Indian in the left temple with a sound so loud and sickening that all that hear it, players and fans alike, will have trouble describing the noise, but will never forget it. Thinking that Chapman has indeed laid down a bunt, Mays fields the ball that comes his way and throws to first baseman Wally Pip (the same Wally Pip that future Hall-of-Famer Lou Gehrig will replace in the Yankees line-up in 1925) to get the first out of the inning, and only then realizes that something else has happened as Chapman, bleeding from his left ear, slumps to his knees in the batter's box and home plate umpire Connolly waves his arms and calls for a doctor's assistance. Two doctors come out the hushed crowd and after several minutes of icing the shortstop's temple, Chapman is able to regain his feet as two Indians lead the injured shortstop across the field towards the entrance to the visitor's clubhouse in center field. Before they make it though, Chapman loses consciousness again and has to be carried off the field (in the clubhouse, Chapman will lapse into unconsciousness yet again and the decision is made to put the shortstop on a stretcher and get him to a hospital as quickly as is possible ... leaving for the hospital Chapman has two concerns ... one is that the Indian's traveling secretary, Percy Smallwood, is still holding the diamond ring the shortstop had given him for safe keeping that he has recently bought for his wife, and that word be given to Mays to "not worry" as Chapman believes he'll be fine). When the game gets underway again, Harry Lunte comes into the game for Chapman (getting hurt himself later in the season, the Indians will bring up a prospect from the minor leagues to replace a .196 hitting Lunte, a youth named Joseph Wheeler "Joe" Sewell that will play shortstop for the Indians for the next ten years, finishing his career with the New York Yankees in 1933 with a career batting average of .312 with 2,226 hits, 1,054 RBIs, two world championships, and several records for his ability NOT to strikeout, setting a modern season record by whiffing only three times during the entirety of the 1932 season ... inducted into the Hall-of-Fame in 1977, Sewell will state the reason he believes he makes it into the Hall ... "I would forget I was Joe Sewell and imagine I was Ray Chapman, fighting to bring honor and glory to Cleveland.") and Mays continues to pitch, allowing a fourth run to score when Gardner and O'Neill hit back-to-back singles. In the ninth inning, the Yankees stage a comeback and finally put three runs on the scoreboard on a Babe Ruth single to right field, a walk to Del Pratt, a double just inside the right field foul line by Bodie, and single by Ruel, but the rally falls just short (when Speaker checks in with Coveleski to see if the pitcher should be replaced, the Indian ace says he can get the final out of the game, and good to his word, induces pinch hitter Lefty O'Doul into a game ending ground ball) and the game ends as a 4-3 Indian victory.

Connolly

Lunte & Sewell

Box Score For The Game

There is no celebrating though in the Cleveland locker room where the team quickly showers and dresses, before following their fallen comrade to the nearby St. Lawrence Hospital (it is only half a mile away from the Polo Grounds) where a team of doctors decide surgery will be necessary to relieve pressure on Chapman's brain (Speaker will call Chapman's wife with the news of her husband's injury, and she will rush to the Cleveland train depot and take the first locomotive leaving for New York City). At 12:29 in the evening, Dr. Thomas Merrigan, the hospital's surgical director, begins a 75 minute operation on the three and a half inches long depression fracture on the left side of Chapman's skull, removing an inch and a half piece of cranium bone from the shortstop (looking at the damage the pitch has done, the doctor finds that the impact has not only damaged the left side of Chapman's brain, but has also wounded the organ's right side where the force of the hit has bounced his brain off the interior right side of his skull, leaving several blood clots behind. Operation completed, it at first appears that Chapman might recover from the trauma when his pulse normalizes and his breathing becomes easier. Hearing the news, Chapman's teammates retreat to their hotel, all hoping that the morning will find their comrade in much better shape. Not to be however, when the Indians wake up the next morning they are horrified to receive the news that Chapman has passed away at 4:40 in the morning of the 17th (arriving in New York later that morning, Kathleen Chapman, pregnant with the couple's daughter, will be greeted at the train station by a Philadelphia priest and the shortstop's friend, and receiving the news that she has become a widow, will faint to the ground at the news

The Ball

The Big News

Attended by thousands (among them will be members of the Cleveland Indians, who return home for the ceremony, and then get back on a train to continue their August schedule of games) Chapman's funeral takes place on Friday, August 20th at the Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist located in downtown Cleveland on Superior Street with American League president Ban Johnson in attendance. During the service at St. John's, Chapman's best friend, outfielder John Gladstone "Jack" Graney, will become hysterical with grief and have to be restrained before being escorted from the cathedral, and buddy Tris Speaker, filled with grief for the part he played in getting Chapman to play ball one more year, becomes so distraught with emotions that he collapses at the home of Kathleen Chapman's parents and is unable to attend the funeral and enters into a deep depression instead. Afterwards, Chapman is laid to rest at Cleveland's Lake View Cemetery (where over a hundred years after his passing, visitors still leave quarters, poetry, baseballs and other tribute knick-knacks in honor of the shortstop) in a shady part of the 285-acre cemetery that also will be the final resting place of industrialist John D. Rockefeller, crime fighter Eliot Ness, and assassinated 20th U.S. President, James Abram Garfield. Almost matching the darkness of Graney and Speaker, when the Indians return to playing baseball, they go into a funk that lasts for days; playing two doubleheaders at Fenway Park, Cleveland drops three of the four games and will lose eight of their next eleven contests before their love for Chapman helps them right their ship just in time. Dedicating the remainder of the year to their fallen shortstop and paying tribute to him by wearing black armbands for the balance of their campaign, Cleveland closes out the regular season by winning 24 of their last 32 games to finish 1920 with a record of 98 wins and 56 losses, finishing two games ahead of the White Sox and three games in front of the Yankees, finally winning a pennant. The American League representative in the World Series, the Indians face the Brooklyn Robins for professional baseball's overall championship, an accomplishment they achieve by steam rolling the National League team, 5 games to 2 in a clash in which they outscore the Robins 21 to 8, outhit the Brooklyn team, 53 to 44, second baseman Bill Wambsganss will pull off the thus far only unassisted triple play in championship history by catching a line drive off the bat of pitcher Clarence Mitchell (in the eighth inning he will make history again when he grounds into a double play, becoming the only play to have two at bats result in five outs!), stepping on second base to turn second baseman Pete Kilduff into an out, and then tagging out the runner coming from first base, catcher Otto Miller, have Indian outfielder Elmer Smith hit the first grand slam in Series history, and Cleveland pitcher Jim Bagby become the first pitcher in Series history to homer in a game. Each Cleveland player earning a winner's share reward of $5,207, after they clinch the 1920 championship, the team unanimously votes to give a full share of their award money to Kathleen Chapman.

1920 Champs

While Chapman's part in the tragedy ends, Mays becomes baseball's #1 villain ... a crown he seemingly grabs up only moments after beaning the shortstop by continuing to pitch in the game and remaining on the mound while folks are treating the injured Indian, and then in the locker room afterwards, telling sportswriter F.C. Lane of Baseball Magazine that he was ineffective in the game because manager Miller Huggins moved him up a few days in the rotation and because the weather made the balls damp, while stating he is ready to throw again the next day ... BEFORE HE ASKS ABOUT HOW CHAPMAN IS DOING! Later, hearing that Chapman has died, after Mays gives his tear-filled version of the beaning to the New York City district attorney, the pitcher is said to become so depressed by what has happened that he goes into seclusion for ten days (aware of the abuse that might come his way from irate fans, he also manages to avoid being with the Yankees when they go to Cleveland for an important three game series in September (though no one says anything, the game absences obviously effect the pennant race in which the Yankees finish three games behind the Indians). Career in jeopardy with many baseball fans saying they will boycott games Mays plays in (Boston and Detroit will start petitions requesting Mays to be banned from baseball and two umpires issue a statement basically calling Mays the biggest cheater in the league), Ban Johnson finally rules that Chapman's death is a horrible accident and that the pitcher may continue his career. He finishes 1920 winning 26 games, then bests that the following year by winning 27 contests (pitching in the 1921 Series that the Yankees lose to the New York Giants, there will be rumors that Mays has thrown games like the Black Sox of 1919, but nothing is ever proven). Closing out his career with stints on the Cincinnati Reds and New York Giants, Mays goes into retirement as a four-time world champion with a win-loss record of 207-126, 29 shutouts, 862 strikeouts and an ERA of 2.92 at a time when the league average is 3.48 (in his career he also hits five home runs, knocks in 110 runs, and sports a lifetime batting average of .268), stats that are comparable to those that are posted by other Hall-of-Famers like Bob Feller and Carl Hubbell.

Mays

Enshrinement not to be though ... Mays is passed over for membership in the Hall by induction voting sportswriters (a minimum of ten years service required for eligibility, Chapman never makes a ballot because he only plays for nine years), and then, by the Veterans Committee, and rightly or wrongly, he will spend the rest of his life blaming his exclusion on throwing the only pitch in major league baseball history to kill someone (Mays will call the the beaning of Chapman "the most regrettable incident" of his career that he would happily undo if he could. Stating he is guiltless and sleeps well every night, he also passes blame around to other factors and folks ... the weather, the wet day, Yankee manager Miller Huggins, Ban Johnson for forcing tattered balls to be kept in play, umpire Connolly for making him pitch with a wet and beat-up ball ... and even throws shade Chapman's way for causing his own death: "I didn't hit Chapman, Chapman hit hisself. He run into the ball that was over the plate but as high as his head. That's how Chapman got hit."). Already a bitter individual before he becomes a baseball player, his exclusion causes his soul to become even darker, and there will be even more bitter to bathe in during his retirement years. Mays will lose his life savings during the stock market crash of 1929 and worse, his 36-year-old wife, Majorie, in 1934, to an eye infection, leaving him with two young children to raise (he will marry a second wife, Esther Ugstead, in Oregon). Retired but baseball still seemingly in his blood, Mays will pitch two seasons for the Pacific Coast League and the American Association, serves as a baseball scout for twenty years for the Indians, the Milwaukee & Atlanta Braves, and the Kansas City Royals, and opens and runs a baseball school in Oregon (his most successful student will be "Mr. Red Sox" himself, Johnny Pesky). Once a year until his death, Mays also makes a yearly pilgrimage to Hoover High School in San Diego, California where he works with the pitchers in his son-in-law's program ... a partnering that will result six straight years of first or second place finishes, and three CIF championships in five finals appearances. Working with the team again in 1971, Mays comes down with pneumonia and passes away on April 4th at San Diego's El Cajon Valley Hospital at the age of 79 ... all his obituaries mention the Chapman incident of course, typical of all is one headline that reads Carl Mays: Yankee Whose Pitch Killed Batter in 1920 is Dead. Mays is buried at Portland's River View Cemetery.

The family of Chapman also finds additional tragedy after the shortstop's death. Kathleen Daly Chapman, once an avid baseball fan, never attends another game after her husband's death ... a death Kathleen never gets over. On February 27, 1921, Kathleen gives birth to a little girl she names Rae Mae. Moving to California, she will remarry, but still wallowing in grief over the death of her first husband, she doses herself with poison and commits suicide in 1928. A year later, only days after saying her mother has come to in a dream stating they will be together soon, Rae Mae catches the measles and dies a week later.

The Widow

Hayes And His Helmet

Montgomery's Last At Bat

Chapman's Grave

Chapman

No comments:

Post a Comment