9/8/1923 - In a time before all naval ships are equipped with radar, night, fog, wind, currents muddled by an earthquake off of Japan days before (known as both "The Great Kanto" and "The Tokyo-Yokohama" earthquake, the 7.9-magnitude shaking of between four and ten minutes long creates a tsunami 39.5 feet in height, destroys over 570,000 homes, and kills over 105,000 individuals) navigation by dead reckoning, a follow-the-leader mind set, and an extremely treacherous area of central California coastline north of the town of Santa Barbara that had earned the nickname of The Devil's Jaw, all combine to produce what is still the largest peacetime loss of U.S. Navy shipping ... a tragedy that will come to be known as the Honda Point Disaster.

Headlines

The sea always his destiny (relatives fight in the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, and on both sides of the Civil War and his great grandfather was a United States senator and the governor of Kentucky) Edward Howe Watson is born into the Frankfurt, Kentucky family of U.S. Navy Commander and future Rear Admiral, John Crittendon Watson, on February 28, 1874 (at a four acre portion of town called The Corner for its location at a place where the Kentucky River takes a right-angle turn, a wealthy and powerful section of town that thus far has also produced three other naval officers of flag rank, major generals on both sides of the Civil War, a U.S. attorney general, a secretary of the treasury, an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, four governors, and eight United States senators). Granted entrance to Annapolis based on his father's sterling record of leadership in the U.S. Navy (an 1860 graduate of Annapolis, J.C. Watson has a naval career in which he helps save 500 members of the crew of the foundering government transport, Governor, serves as flag lieutenant to Rear Admiral David Farragut at the Battle of Mobile Bay, is wounded by a Confederate shell fragment at Warrington, Florida, serves as executive officer aboard the steam sloop Alaska, has the post of inspector of ordinance at the Mare Island Naval Yard in Vallejo, California, commands the warship Wyoming during that vessel's crossing of the Atlantic with the American exhibits that will be shown during the Paris Exposition of 1878, commands the U.S. Navy's Eastern Fleet during the Battle of Santiago in which the Spanish squadron of Admiral Pascual Cervera is destroyed, serves as Commander-in-Chief of America's Asiatic Fleet, serves as President of the Naval Examining Board, and represents the United States at the coronation of King Edward VII of England in 1902), Edward H. Watson graduates as an ensign from the United States Naval Academy in June of 1895. Beginning his slow climb up the chain of command in the United States Navy, the junior Watson serves aboard a host of different ships and stations ... during the Spanish-American War he is aboard the battle cruiser USS Detroit, from 1912 to 1913 he is in command of the storeship USS Celtic, attends the Naval War College, sees duty as the executive officer of the battleship USS Utah, and serves as the commanding officer of the gunboat USS Wheeling. When the United States enters WWI, Watson first commands the transport Madawaska, then takes over the battleship USS Alabama, aboard which he will receive the Navy Cross for "exceptionally meritorious service." After the war is over, Watson is appointed the U.S. Naval Attache in Japan, and then in 1923, promoted to commodore, takes command of Destroyer Squadron Eleven based in San Diego, California.

Father

Father

Son

Son

Composed of nineteen relatively new Clemson-class destroyers built between 1919 and 1922, the destroyers of Destroyer Squadron Eleven have a fully loaded displacement of 1,308 tons, a length of 314 feet and 4.5 inches, a beam of 30 feet and 11.5 inches, a draft of 9 feet and 4 inches, are driven by the power of 4 boilers (their funnels will earn the ships the nicknames "flush-deckers, four-stackers, and four-pipers) and 2 geared steam turbines turning two propeller shafts that can reach a speed of 35.5 knots, have a range of 4,900 miles, are armed with 4-inch guns, torpedo tubes, and depth charges, and are individually crewed by 8 officers, 8 chief petty officers, and 106 enlisted sailors. Successfully participating in Pacific Battle Fleet maneuvers in the Puget Sound area of the Washington coastline (though not a total success, one destroyer is in a collision during the maneuvers), Watson receives orders to take his squadron back to its home base in San Diego, California, with a scheduled stop in San Francisco. Peace time budget constraints gone for the moment, Watson wishes to make the run in record time and his destroyers, treating the trip as a simulated war run, are allowed to crank their turbines up to a speed of 20 knots. Led by the USS Delphy, where Watson flies his squadron flag, fifteen destroyers (one vessel is in dry dock, two ships leave the previous evening with the squadron tender because they have engine problems and can not meet the cruising speed of 20 knots, and another destroyer testing its smoke prevention system proceeds independently for San Diego) divided into three divisions, leave San Francisco's Pier 15 at 0700, form into columns and head south for home.

USS Delphy

USS Delphy

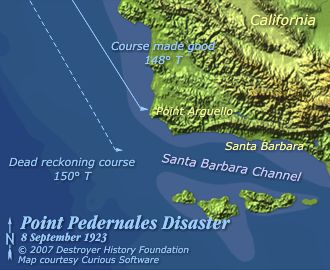

Navigation for the unit is handled by the USS Delphy's captain, Lt. Commander Donald T. Hunter (who taught navigation at Annapolis for two years). But there is a problem, Hunter is not an advocate of the new radio navigation (RDF) aid the U.S. Navy has recently begun using ... instead, the sail down the coast will be made by dead reckoning, estimating the squadron's position by course and speed as measured by propeller rotations per minute with fixed positions checkpoints at five lighthouses between San Francisco and San Diego ... Pigeon Point, Point Sur, Point Pedro Blancas, Point Arguello, and Point Concepcion. At 1130, Pigeon Point is spotted one mile to port ... the last solid position fix the squadron is able to take. When Hunter receives RDF information from Point Arguello at 1415, the position information is not believed, and as the information is checked, the squadron goes by Point Sur and Point Pedro Blancas without fixing its position (despite the efforts of the Delphy's assigned navigator, Lieutenant J.G. Lawrence Blodgett, who also advocates taking depth soundings but is told no, because it will slow the exercise), while Watson spends most of the time in his cabin, discussing the Japanese Navy with a civilian guest passenger, career diplomat Eugene Dooman, content that Hunter will guide them through the Santa Barbara Channel without incident, unaware that when he orders Squadron Cruising Formation #18 at 1627, putting his destroyers in a single, line ahead column, his ships are not at the entrance of the channel, but are three miles north of Point Arguello and only a mile and a half off the coast (Hunter's miscalculation of where the squadron is caused by no account be given to the current changes caused by the "Great Kanto" earthquake days before in Japan, a heavy following sea in which the propellers broach, preventing an accurate accounting of the Delphy's prop revolutions and hence the ship's speed, using estimates of the ship's speed at 21 knots, when it is actually closer to 19 knots, and the presence of a brisk wind blowing west-southwest. Fate sealed, at 2100, Watson and Hunter have the squadron turn east, sending 14 destroyers directly at the ship hungry cliffs and rocks of Point Pedernales (experiencing boiler problems, the USS John Francis Burnes drops out of formation before the turn).

Pigeon Point Lighthouse - Last Fixed Position

Pigeon Point Lighthouse - Last Fixed Position

Oooops!

Oooops!

A menace to navigation from the time 16th Century conquistadors and Franciscan missionaries begin exploring the California coast, the shipping eating portion of cape that Watson and his destroyers are headed for acquires many names over the years ... Point Pedernales (from a Spanish description of the area being as tough as flint), Honda Point (part of a lariat, the catch is seagoing vessels though), "The Graveyard of the Pacific" (again a reference to the many vessels that make the area their final resting place), and "The Devil's Jaw" (ready to bite into any ships foolhardy enough to enter the area). All effectively describe the danger waiting for the unwary ... hard igneous rock in the form of steep, 60-foot cliffs with almost no beaches, and in the water, a satanic collection of huge boulders, submerged pinnacles, and intermittent reefs all swept by winds, constant wave action, and sometimes huge breakers. On 9/8/1923 the area is most infamously known as the place where the gold bullion carrying ($150,000, now worth over $4,285,000), 275-foot steam-powered paddleboat, SS Yankee Blade goes down in September of 1854, killing 40 of its 1,000 passengers (all because of a foolish speed bet the captain has made). Before the next day dawns, the wreck wreck will have company, and two more names will be added to the lexicon of the area ... the aptly named Destroyer Rock and the Woodbury Rocks for where the USS Woodbury goes under.

SS Yankee Blade

SS Yankee Blade

Earthquake Devastation

The dark and fog hiding the coast from view, the USS Delphy turns and is soon lost to sight of the rest of the squadron. Following orders and the leader, three hundred yards behind, the USS S.P. Lee makes her turn, and in turn, is followed by the USS Young, and four minutes later, at 2104, the tragedies begin. Although third in line, the first casualty is the USS Young ... she hits a submerged pinnacle of rock that tears her starboard side open and in a matter of minutes she capsizes into the cold waters of the Pacific. The next casualty is the USS Delphy ... suddenly aware of her danger, she crashes bow first into the rocks of the Devil's Jaw as her sirens begin alerting the squadron of its danger and Watson sends out two radio warnings to his destroyers, one to keep clear to the westward, and the other to make a "nine turn" 90-degree course change to port. Behind her, the USS S.P. Lee sees the lead destroyer come to a sudden stop and she sheers to port (left) to avoid a collision and comes to a stop herself, running aground on the coast. Warnings received too late, the USS Woodbury and the USS Nicolas slam into Honda rocks.

USS Young

USS Delphy

USS S.P. Lee .

USS S.P. Lee .

USS Woodbury

USS Woodbury

USS Nicholas

USS Nicholas

Next in line is the USS Farragut. Suddenly coming upon the chaos in front of him, the destroyer's captain slows, stops, and then orders emergency full astern ... which causes a sideswipe collision with the following USS Fuller, which slams into several rocks and loses all power, while the USS Farragut manages to find its way to deeper waters. Coming up behind, the captains of the USS Percival and the USS Somers take quick action and manage to escape the rocky trap, although the USS Somers suffers serious damages steering out of the area. The USS Chauncey will not be as lucky. Alerted of the danger, before the destroyer can maneuver out of the area, she is caught by the powerful outgoing undertow of the area that sends her into the wreckage of the overturned USS Young and one of its exposed propellers, a collision that tears open the destroyer's engine room and immediately causes the vessel to lose all power. Carnage complete, the last vessels of the squadron, the USS Kennedy, the USS Paul Hamilton, the USS Stoddert, and the USS Thompson all manage to avoid entering the area.

USS Fuller

USS Fuller

USS Chauncey

USS Chauncey

Calm to crisis in seconds, the destroyer sailors move from their normal duties in a standard cruising formation to fighting for their lives and the lives of their crewmates instantly ... a tribute to the training, discipline and courage of the men of the United States Navy. Pinned against rocks on her starboard side, stern first to shore, the captain of the USS Nicholas decides to keep his crew aboard their stricken destroyer until daylight. The crews of the USS Woodbury and the USS Fuller, aground the farthest from shore, find temporary refuge on a large chunk of lava, while the men of the USS Delphy and the USS Chauncey are able to shelter on a narrow ledge below a 60-foot cliff ... a 60-foot cliff which a handful of intrepid sailors somehow climb, and then throwing ropes down, begin rescuing other sailors. Most torn apart in the disaster, the surviving members of the capsized USS Young cling to their ship's slippery port side, many by holding on to porthole windows they have to smash open. When the powerless USS Chauncey is swept by the wreck of the USS Young, the men are able to abandon their ship, and using a lifeline (set up when Chief Boatswain's Mate, Arthur Peterson, who swims from the USS Young to the USS Chauncey with a line ... an act of courage that will allow 70 men in 11 trips to move to safety), pull themselves on to the crippled destroyer before moving to the solid ground of shore. Coming to the aid of the survivors, the undamaged destroyers, men from a local railroad work crew, and fisherman from the nearby town of Lompoc participate in the rescue efforts. A miracle of luck, courage, and determination, although almost every one of the 800 sailors of Destroyer Squadron Eleven suffer from shock and cuts and bruises caused by the rocks, only 23 perish ... three from the crew of the USS Delphy, and 20 from the USS Young.

Tragedy Mapped

Arthur Peterson

Northernmost - The USS Nicholas (L) & USS S.P. Lee

Northernmost - The USS Nicholas (L) & USS S.P. Lee

USS Delphy Foreground, Capsized USS Young Behind, Listing USS Woodbury, And Funnels Behind Of USS Fuller

USS Chauncey

Not amused at the worst peacetime naval disaster in its history and the loss of seven destroyers, a seven-officer Navy court-martial board, under the direction of Vice Admiral Henry A. Wiley (commander of the battleship divisions of the U.S. Navy's Pacific Battle Fleet) convenes in early November and brings charges of negligence and culpable inefficiency to perform one's duty against eleven officers, the largest court martial in the U.S. Navy's history (before the court-martial, the Navy gathers 19 days of evidence and praises 23 officers and men for their heroism during the incident). The court-martial eventually finds the disaster to be due to "bad errors and faulty judgments" on the part of Watson (he is defended at the proceedings by Admiral Thomas Tingey Craven), and he, Hunter, and Lt. Commander H.O. Roesch (commander of the USS Nicholas) are found guilty, but politics involved, Rear Admiral S.S. Robison sets aside Roesch's conviction. Watson and Hunter are not so lucky and they are stripped of their seniority and lose all possibilities of future promotions with Watson ending his naval career in 1929 as Assistant Commander of the Fourteenth Naval District in Hawaii (he dies in 1942). Trapped in a minor posting, Hunter also retires from the U.S. Navy in 1929. The other eight officers are all acquitted (two will go on to command battleships), and the court-martial board additionally recommends Commander Walter G. Roper be given a letter of commendation for keeping his division of the destroyer squadron out of the Devil's Jaw debacle.

Craven .

Craven .

Watson

Putting the disaster behind itself, the U.S. Navy strips the wrecks of records, equipment, and records, removes the destroyers from its list of active ships, and sells the remains to a local salvage company for $1,035 (at the time, the value of the seven lost destroyers was $13,000,000). They remain at Honda Point to this day, now sunken monuments to a disastrous naval blunder that can be visited with permission (the site is now part of Vandenburg Air Force Base) and good dive equipment. Remembering the event, on a bluff overlooking the site there is a plaque and memorial, with the memorial including the ship's bell from the USS Chauncey. Nearby, outside the Veterans' Memorial Building in Lompoc, a propeller and propeller shaft from the USS Delphy are on display.

Memorial

Prop

9/8/1923 ... in a horribly fatal mistake, Destroyer Squadron Eleven forgets a basic caution that a naval officer reviewing the case will sum up simply, "The price of good navigation is constant vigilance." Indeed and amen!

Seven Dead Destroyers

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete