Slovik

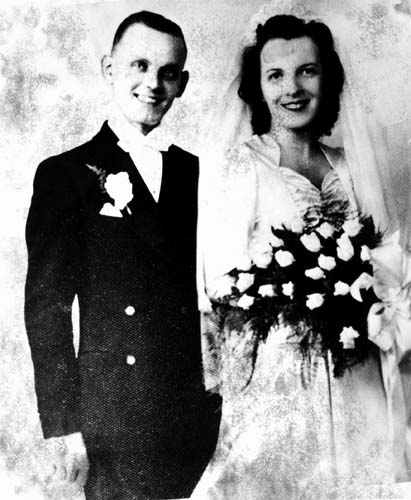

Born into the Polish-American family of Anna and Josef Slowikowski in 1920, Slovik seems destined for a short and tragic life ... he is first arrested at the age of 12 for stealing brass from a Detroit foundry, drops out of school at 15, and goes on to establish a criminal resume that includes petty theft, breaking and entering, disturbing the peace, car theft, and drunk driving, is placed on probation five times, is sentenced to prison twice. Paroled in April of 1942, with workers at a premium due to America's participation in World War II, as being deemed 4-F, unfit for duty due to his criminal record, Slovik finds work and love in Dearborn, Michigan, where he is employed at the Mortella Plumbing and Heating Company, and meets his wife, the company's bookkeeper, Antoinette Wisniewski (she is five years his senior). Living with her parents, Slovik keeps out of trouble while holding down a job as a shipping clerk for the DeSoto division of the Chrysler Car Company. Shortly after the couple's one-year anniversary their married bliss falls apart, when the U.S. government needing more men to fight the war, reclassifies Slovik as fit for duty, drafts him, inducts him int the Army, and sends him to Camp Wolters, Texas for basic training.

The Sloviks

The five-foot-six, 138 pound recruit does not like being a soldier, and in a letter to his wife, describes the experience as like being in jail ... only worse. Despite his disdain for the service, on 7/25/1944, Slovik is shipped off to England (during his sea voyage, he tells a fellow soldier he doesn't know why he is cleaning his rifle, as he has no intention of ever firing the weapon), then sent to the Third Replacement Depot in France. Ticketed to be a replacement member of Company G, 109th Regiment, 28th Infantry Division (the famous Keystone Division that can trace its roots back to the Pennsylvania days of Benjamin Franklin), Slovik takes a three-hour ride through the carnage left behind during the horrific Battle of the Falaise Pocket (a two-week nightmare that costs the Germans 450,000 men and 209,000 Allied soldiers), and then arrives in Elbeuf, France at night just as the town is being shelled. Finding immediate refuge, Slovik is separated from the other replacements (along with Private John P. Tankey), and when the 109th moves out in the morning, no one with the unit notices that the two men are missing ... which is just fine with Slovik, who spends the next six weeks driving trucks, helping with the cooking, and guarding German prisoners for the unit that has moved into Elbeuf, the military police outfit, the 13th Canadian Provost Corps. Trouble begins however, when the Canadians get a new commander who immediately wants to know why two Americans are doing duty with his unit.

Camp Wolters

Battlefield Detritus

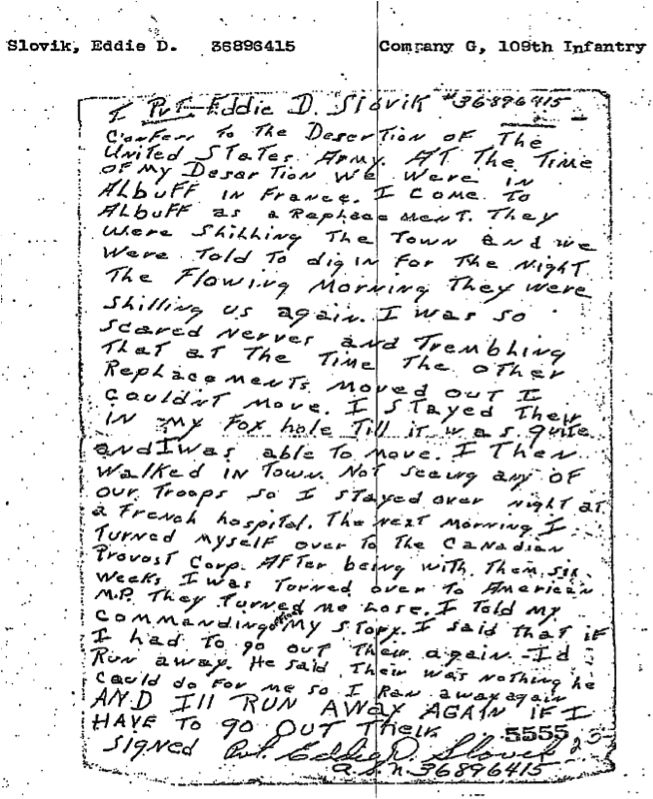

Sent back to their units on 10/7/1944 (about to enter the maelstorm of the heavily defended Hurtgen Forest), no charges are filed against either man, and Tankey returns to duty and eventually will be wounded in combat and survive the war. But Slovik is having none of it, tells he company commander, Captain Ralph Grotte, he is "too scared" to fight and requests a transfer to a non-combat unit or he will run away. Request denied, the next day, after Tankey fails to dissuade him, believing he will just receive jail time, which he knows he can handle and will leave him alive, Slovik trudges several miles to the rear, and turns himself in for desertion to 112 Military Government detachment stationed in Rocherath, Belgium, handing a confession he has hand-written on a piece of paper to a cook, Private William O. Smith that states he is guilty and will leave again if forced back into a front line unit (the cook in turn takes him to an MP, the MP takes him to his company commander, and the company commander tells him to tear up the note and get back to the front ... which Slovik refuses to do). Returned to his unit in handcuffs, the battalion commander, Lt. Colonel Ross C. Henbest gives Slovik another chance to return to his unit and get out of his predicament, but the offer is refused, as is the one that comes from the division's Judge Advocate General, Lt. Colonel Henry Sommer that charges will be dropped if Slovik rejoins his unit, or accepts a transfer to a different combat unit. Slovik states, "I've made up my mind. I'll take my court martial," which is a big mistake.

Confession

Court Martial

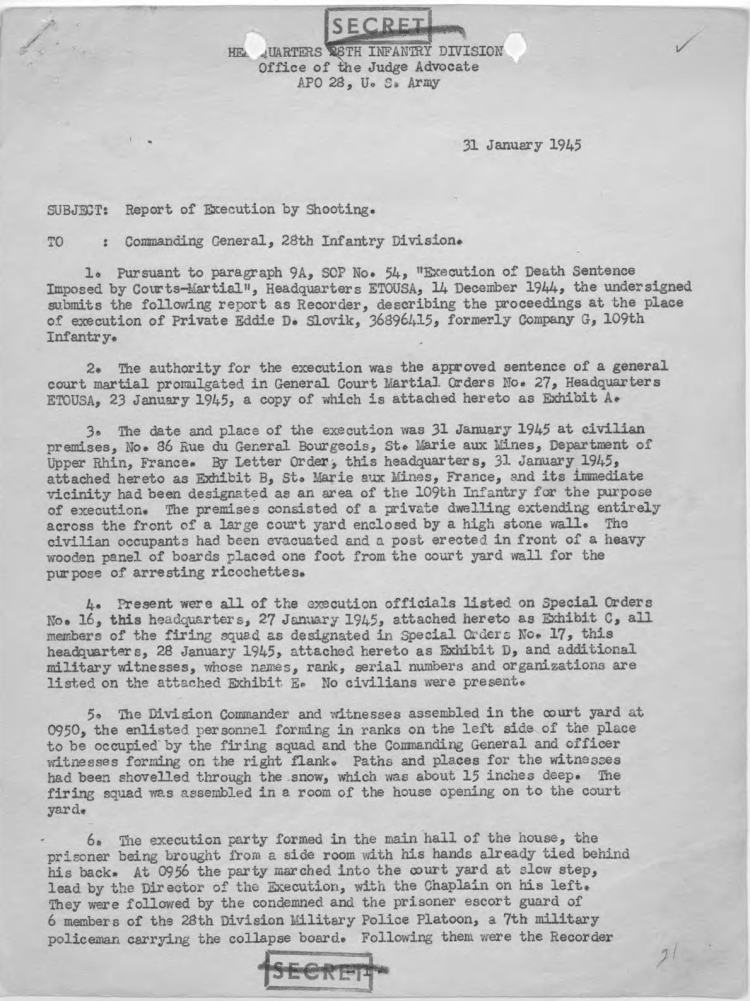

A slam dunk conviction, Slovik (who refuses to testify) is tried before nine combat officers from divisions other than the 28th Infantry (because they are in combat), prosecuted by Captain John Green (who presents a five witnesses who testify to Slovik's intentions to desert, along with the confession), he is fruitlessly defended by Captain Edward Woods. The trial takes all of only one day (and that is overstating things ... the trial lasts just over an hour) and Slovik is unanimously found guilty and sentenced to death. The death sentence normally not carried out though, this time, with the Battle of the Bulge and the Hurtgen Forest freshly in mind, and with it, the knowledge of the deaths of thousands of American soldiers, multiple times given a chance to do his duty, the verdict is first verified by the division's commander, Major General Norman Daniel "Dutch" Cota, and then, on 12/23/1944, confirmed by the Supreme Allied Commander, General Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower.

Cota

Eisenhower

Unrepentant, Slovik states to his guards, "They're not shooting me for deserting the United States Army, thousands of guys have done that. They just need to make an example out of somebody and I'm it because I'm an ex-con. I used to steal things when I was a kid, and that's what they are shooting me for. They're shooting me for the bread and chewing gum I stole when I was 12-years-old." Per military custom, on 1/31/1945, Slovik's uniform is stripped of all military identifying insignia, buttons, and any other accouterments (he is allowed a GI blanket to be wrapped around his shoulders to offset the morning's cold), and he is walked out of his cell by a four-man detail (delayed a day by a snowstorm, they do not arrive in Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines until 7:30 in the morning on the day of execution) to the courtyard of a house selected for having a high brick wall that discourages any unwanted witnesses from watching. There, using web belts to prevent any movement (one around and under his arms, another around his knees, and a third securing his ankles), he is lashed to an 6-inch wide by 6-foot tall post (with a sheet of wood behind it to prevent any chance of bullets bouncing back off the masonry). When the attending chaplain, Father Carl Patrick Cummings asks Slovik to pray for him when he gets to Heaven, Slovik replies with his last words ... "Okay, Father. I'll pray that you don't follow me too soon." Black hood placed over his head (it has been sewn by a local French women that doesn't know its purpose), at the command "Fire," the 12-man execution squad sends a volley into the condemned man ... eleven live rounds and one secret blank so no one will ever known if they fired the fatal shot, Slovik is hit by all eleven bullets, and takes wounds that range from the neck region to the left shoulder and chest to his left arm ... four are deemed fatal, but despite the wounds, Slovik does not die immediately. In the process of reloading to fire another volley, Slovik passes away 15 minutes after being fired upon.

Movie Recreation

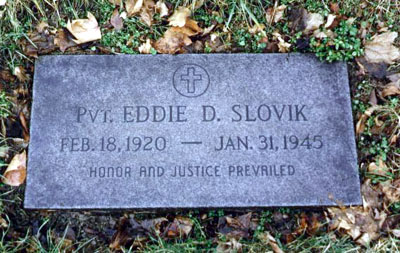

Example made, the Army does a very poor job promoting the execution ... the 109th Regiment announces Slovik's death, but only to its own men, Cota and Eisenhower make no note of the private's death, his wife is only told he died a "dishonorable" death (she will receive a $70,000 payment from the government in 1978 and she petitions the United States to return Slovik's body until her death in 1979 at the age of 64 ... she also petitions seven different presidents to pardon her dead husband, but none of them ever do), and famous Eastern Theater Army historian, S. L. A. Marshall doesn't find out about the death until 1954. Dead, Slovik is first buried in Epinal, France, then in 1949, it is moved to Plot E of the Oise-Aisne Cemetery and Memorial in Fere-en-Tardenois, France, where it is marked by only a number, alongside 95 other soldiers executed during the war for the crimes of rape and murder. In 1987, Polish-American WWII veteran and former Macomb County Commissioner, Bernard V. Calka, finally persuades President Ronald Reagan to allow Slovik to return to the United States (Calka pays $5,000 for the body to be exhumed, transported back to Detroit, and be reburied next to his wife). The tragic soldier now resides at the Woodmere Cemetery in Row 3, Grave 65 of Plot E.

Happier Days

Mrs. Slovik - 1974

Detroit Cemetery

"eleven live rounds and one secret blank so no one will ever known if they fired the fatal shot" The M1 fires a 30.06 round that has a substantial recoil. A blank round has no recoil. The only one that knew that he did not fire the fatal shot is the one with the blank round.

ReplyDelete