5/4/1942 to 5/8/1942 - After taking a massive bloody nose from the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) during the surprise attack on the American naval base of Pearl Harbor (12/7/1941), and along with Great Britain, being on the wrong side of a series of military disasters that follow in which Japanese forces attack and take possession of Malaya, the Philippines, Singapore, the Dutch East Indies, Wake Island, New Britain, Guam, and the Gilbert Islands, the United States Navy and it's airmen, start to turn the tide of the conflict in the Pacific at the Battle of the Coral Sea. A five day clash that provides a window on to how the ocean war will be fought for the next four years, the battle will be the first time opposing fleets will neither sight, nor fire upon each other (all the damage to both sides in the encounter comes from carrier planes operating from somewhere "over the horizon"), and the fight will mark the first time during WWII in which a major Japanese offensive is turned back.

The USS Lexington Blows Up

One of the world's most beautiful bodies of water, the Coral Sea (so named for the coral reefs guarding the northeast coast of Australia) consists of the vast wetness to be found bounded in the west by the east coast of Queensland (the portion that includes the world's largest reef system, Australia's Great Barrier Reef), by the New Hebrides islands (now the Republic of Vanuatu) and New Caledonia, northeast by the southern extremity of the Solomon Islands, and by the southern coast of eastern New Guinea. Sporting 1,850,000 square miles of surface area, the Coral Sea's waters merge with the Tasman Sea in south, the Solomon Sea to the north, the Pacific Ocean to the east, and to the northwest, to Arafura Sea through Torres Strait (the Sea's average depth is 7,854 feet ... it's maximum being 29,990 feet). A warm climate area of over 1,000 islands, the region is known for the richness of it's avian (200 species of birds) and aquatic wildlife (30 species of whales, dolphins, and porpoises, 6 species of sea turtles, 17 species of sea snakes, 1,500 species of fish, including 125 species of shark, stingray, and skate), it's many fishing cultures and customs, and it's frequent rains and occasional tropical cyclones. In the spring of 1942, the region will also be known for the battle that takes place there between the pilots, sailors, and soldiers of the United States and Imperial Japan.

The Locale

Natural Park Of The Coral Sea

1942

Already part of the IJN's plan to use conquered regions about the Pacific to establish perimeter defensive rings to defeat or bloodily exhaust Allied counterattacks, in the weeks following the blooding of the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor, the Japanese finalize their plans to invade Port Moresby in New Guinea and take the anchorage of Tulagi in the nearby Solomons as a prelude for next invading northern Australia in an operation simply dubbed "MO." Assigning assets to the operation, the IJN will have 2 fleet carriers (sister ships, the new aircraft carriers Shokaku "Soaring Crane" and Zuikaku "Happy Crane ... Shokaku is commissioned on 8/8/1941 and is 844 feet and 10 inches long, takes to sea 84 aircraft, and is manned by a crew of 1,660, while Zuikaku is commissioned on 9/25/1941 and is also 844 feet and 10 inches in length, and takes the same amount of men and planes to sea as Shokaku), a light carrier (Shoho "Auspicious Phoenix" is 674 feet and 2 inches in length, is crewed by 785 Japanese, carries to sea 30 planes and is commissioned on 11/30/1941), 9 cruisers, 15 destroyers, 5 minesweepers, 2 minelayers, 2 submarine chasers, 3 gunboats, an oiler, a seaplane tender, 12 transports, and 139 carrier aircraft with which to accomplish its goals (at the same time, in the northern Pacific a even more formidable fleet is being gathered for the Japanese invasion of Midway Island). Designated CarDiv 5, in command of the Japanese fleet is a submarine man, 50-year-old Vice Admiral Takagi Takeo (a veteran of the invasion of the Philippine Islands, the Japanese landings in the Dutch East Indies, and the winning commander at the Battle of the Java Sea) who unexperienced with air operations, chooses a heavy cruiser for his flagship and delegates control of carrier operations to his close friend, 53-year-old Rear Admiral Hara "King Kong" Chuichi. And in overall command of the operation, based out of his Rabaul headquarters on the island New Britain is Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto's friend and protege, 52-year-old Vice-Admiral Shigeyoshi Inoue. On May 1, 1942, CarDiv 5 begins moving south from the huge Japanese naval base at Truk Lagoon to put Operation MO into effect ... unaware that there are already American ships steaming the Coral Sea looking for a fight.

Takeo & Hara

Shokaku

Zuikaku

Japanese plans deciphered by code breakers working in Hawaii for 39-year-old Lt. Commander Edwin Thomas Layton and 41-year-old Captain Joseph John Rochefort, 57-year-old Admiral Chester William Nimitz, commander-in-chief of the United States Pacific Fleet, combines two small task forces into a single unit that can oppose the INJ presence in the Coral Sea for Operation MO with 2 fleet carriers (honoring the American Revolution's start and finish, the aircraft carriers are the USS Lexington, "Lady Lex," an 888 foot long carrier commissioned in December of 1927, crewed by 2,791 men and carrying a complement of 78 planes, and the USS Yorktown, a 824 foot and 9 inch long carrier commissioned in September of 1937, crewed by 2,217 men and carrying 90 planes), 8 cruisers, 14 destroyers, 2 oilers, and 128 aircraft. Responsible for commanding the Allied fighting ships is 57-year-old Medal-of-Honor winner (for the 1914 rescue of refugees from the transport Esperanza at the Mexican port of Vera Cruz), Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher (U.S. Naval Academy Class of 1906). Without a command when Task Force 11 is combined with Task Force 17 into Task Force 17.5, Fletcher appoints his friend and Annapolis classmate, Rear Admiral Aubrey Wray Fitch, to be the tactical air officer for both the Lexington and the Yorktown (having participated in the Doolittle bombing raid on Tokyo that takes place on April 18, 1942, the aircraft carriers USS Hornet and USS Enterprise will not be available for the upcoming Coral Sea operations). Left to decide the specifics of how he will accomplish the mission he is given, Nimitz orders to Fletcher are that the task force he is commanding is to "... assist in checking further advance by enemy ... by seizing favorable opportunities to destroy ships, shipping, and aircraft." Orders given, received, and acted upon, to maintain the surprise he believes he can give the Japanese, Fletcher calls for radio silence among his force while awaiting the code breakers at Pearl Harbor providing him with the most accurate location of the advancing Operation MO warriors. Instead, the information Fletcher has been waiting for comes from a patrol of Australian planes that report on May 3rd of sighting six big Japanese warships in the Solomon Islands, gathering for the Tulagi portion of Operation Mo. Leaving Lexington to continue it's refueling at sea from the American oiler Tippecanoe (the nearest base oil is over 600 miles away), Fletcher steams all night at full speed to the north so his force can launch an early morning attack on the Japanese ships gathering off Tulagi. With the launch of 28 dive bombers and 12 torpedo planes from the deck of the Yorktown, the Battle of the Coral Sea begins on May 4, 1942.

Nimitz Formally Taking Command At Pearl Harbor - 12/31/1941

Fletcher & Fitch

Lexington

Yorktown

Eager for shipping to attack, when Fletcher's raiders reach the Tulagi anchorage at dawn of the 4th, they mistake an armed minelayer (Okimoshima) and two destroyers for being three cruisers ... eager but not accurate, American fliers unleash thirteen 1,000 pound bombs and eleven torpedoes at the minelayer, but fail to sink the Japanese ship. In three separate attacks that Monday on Japanese shipping at Tulagi, Yorktown pilots will drop seventy-six 1,000 pound bombs on IJN targets, but score only eleven hits, sinking a destroyer, three minesweepers, and four seaplanes, at a cost of two American fighters (the pilots are recovered by the destroyer, USS Hammann) and a dive bomber and it's two-man crew (the destroyer, USS Perkins searches the area in vain for the two men). Post battle analysis will find the inaccuracy of the American bombs to have resulted from a mix of causes that include the inexperience of the pilots involved, the attacks being made piecemeal and uncoordinated without the air group commander, Lt. Commander Oscar "Pete" Pederson flying with his team (he has been kept on the Yorktown by the carrier's captain, Elliott Buckmaster, who wants the flier to remain on board to serve as the carrier's fighter director), and the windscreens of the group's Douglas SBD ("Scout Bomber Douglas') Dauntless dive bombers fogging up on their attack dives. The element of surprise now lost to the Americans, Fletcher regroups with the Lexington and takes his task force southwest towards New Guinea to intercept the MO Operation invasion force (out of fuel, Tippecanoe will be sent back to Pearl Harbor, while the Neosho is sent south, escorted by the destroyer, USS Sims), unaware that the Japanese plan is two days behind schedule because of a delay caused by delivering eight Mitsubishi Zero fighters to Rabaul during a storm and that Takagi's carrier force is to the northwest of Fletcher's command, and still out of range (neither side making contact, the two forces come within seventy miles of each other). For two days the two sides fruitlessly search for each other before each discovers the other on Thursday, May 7, 1942.

American Dive Bombers Returning To Yorktown

After Their Tulagi Raid

Wreckage Of The Japanese Destroyer, Kikuzuki -

Sunk Off Tulagi On 5/4/1942

In the darkness just before dawn, both task forces once more send scout planes aloft, each seeking to land the first blows of the battle. Flying a Dauntless dive-bomber off the Yorktown, 29-year-old Lieutenant John Ludvig Neilsen of St. Paul, Minnesota is searching for the Japanese amid the islands off the eastern tip of New Guinea when he spots an opposing INJ scout in the form of a Aichi E-13A "Jake" float plane, and wishing to prevent the observer from alerting higher ups of the presence of American carrier planes, shoots the scout down twenty feet above the waves of the South Pacific (on the flight, Neilsen's back-seat gunner is recent Annapolis graduate Lt. Walter Straub). Regaining altitude and continuing their patrol, 15 minutes later near the Louisiade archipelago's Misima Island, Straub spots the wakes of INJ surface ships which Nielsen confirms to be two cruisers and four destroyers. Trying to alert the fleet though proves to be problematic; the message can't be sent by the plane's long-range radio because the Dauntless' antenna has been shot away dogfighting with the float plane it shot down and with only short-range radio available, it is not until 8:15 in the morning that news of the sighting is received aboard the Yorktown. Just the information he has been waiting for, Fletcher turns his task force north to get within range of the Japanese and at 9:26 a.m., the first plane of a ninety-three aircraft raid is in the air, as Fletcher stands on the bridge wing of the Yorktown screaming at his pilots through a bullhorn, "Get that goddamn carrier!" A few minutes later Neilson is over the Yorktown and has Straub drop another sighting report to the carrier via a bean-bag and the discovery is made and then verified when Nielsen lands that two cruisers and four destroyers reported sighted has been relayed as a sighting of two CARRIERS and four CRUISERS (the code table Straub has used for his message is misaligned). Deciding not to recall the raiders when a report comes in from that land based Allied bombers have also made a fleet sighting in the same region and that his men should attack whatever shipping is actually in the Misima Island area, the admiral's decision will result in an attack on the small fleet screening the main invasion force (reporting to Fletcher upon landing on the Yorktown, Neilsen is chagrinned to be berated by the man for misidentifying the ships spotted, "Young man, do you know what you have done? You have just cost the United States two carriers!" ... not so of course in hindsight and when the days events are fully analysed, the pilot will be awarded a Navy Cross for his actions).

Lt. Nielsen & Lt. Straub

And while those events are taking place for the Americans, still searching for Fletcher's fleet, the Japanese prove they are equally susceptible to miscommunications and mistakes. Receiving a report that his scouts have spotted a carrier and a cruiser, Takagi and Hara have launched a raid of seventy-eight aircraft (36 dive bombers, 24 torpedo planes, and 18 Zero fighters all under the command of veteran Shokaku dive bomb pilot, 35-year-old Lt. Commander Kakuichi Takahasi) from their carriers at the American shipping to their south, but a major error has been made ... the carrier is actually the almost empty oiler Neosho, captained by 47-year-old Commander John Spinner Phillips (Phillips will survive the battle and live to be 80-years-old, dying in 1975 at the Bethesda Naval Hospital ... floating in an open boat for four days after the attacks on the Neosho, when a Canadian rescue plane finally spots him and asks whether he needs assistance, the commander responds with a sarcastic question of his own, "What do you think?") and the cruiser is the destroyer Sims, captained by 41-year-old Lt. Commander Wilford Milton "Buster" Hyman (for his leadership as his ship goes down while still firing its guns, Hyman will win a Navy Cross, but perishes in the 5/7 attacks on his ship). Arriving at the contact location, the Japanese realize their mistake, search for better targets for ninety minutes, and when they find none, unleash their wrath on the two American ships present, sending the Sims to the bottom from three bomb strikes that break the ship in half (only 15 men from her crew of 252 will survive the pasting, none of them officers) and hitting Neosho seven times (and once in the stern by a wounded dive bomber crash diving into the oiler), damaging her so badly that she is barely able to stay afloat, saved mostly by the reserve buoyancy in her partially empty oil tanks (she finally gives up the ghost and is scuttled four days later by torpedoes and gunfire from the destroyer USS Henley <123 sailors are also rescued>, but not before she shoots three of her Japanese aerial tormentors out of the sky).

Phillips & Hyman

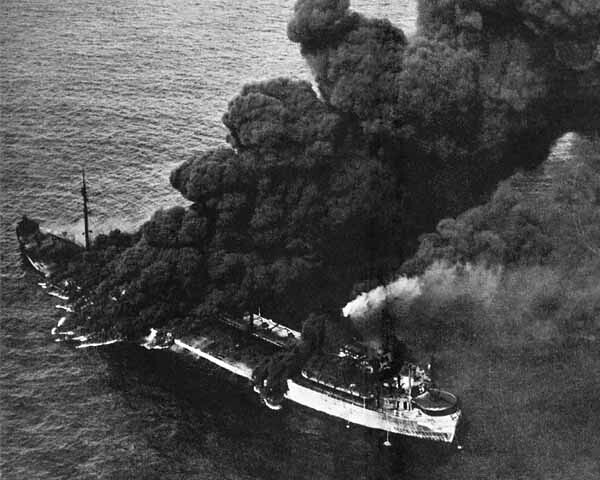

Neosho Aflame

Though the move to relocate the Neosho to a safer locale has backfired horribly, Fletcher's gamble to not recall his attack force after he finds out that they are not heading for Takagi's carrier fleet (other than criticism from his peers and historians, the admiral also suffers no repercussions for breaking his own orders for radio silence, or placing the small surface force of three cruisers and three destroyers of Royal Australian Navy Rear Admiral John Gregory Crace guarding the Jomard Passage giving access to Port Moresby without any air cover) pays off when the raiders from the Lexington and Yorktown spot the cover fleet for the MO invasion of New Guinea (commanded by Rear Admiral Arimoto Goto), featuring the light carrier Shoho, at 11:00 in the morning. Birds of prey gathering overhead, the raiders are delighted to discover that the Japanese ships are protected by only six fighter planes. Lexington pilots going in first as planned, roughly fifteen minutes later the Shoho is assaulted by the dive bombers and torpedo planes of 43-year-old Group Air Commander William Bowen Ault and 36-year-old Lt. Commander Weldon Lee "Hammy" Hamilton. Wild maneuvering by Captain Ishinosuke Izawa that has the Japanese carrier complete a full circle turn to port allows the Shoho to survive its first encounter with the carrier pilots of the United States Navy, but it is only a matter of time before torpedoes dropped from fifty feet above the water and thousand pound bombs dropped at about 2,500 feet from 70-degree angle dives begin striking the carrier; a situation that becomes even more dire for Shoho when the Yorktown pilots, led by 38-year-old Lt. Commander William Oscar Burch Jr. take their turn at hitting the Japanese ship. Quickly turned into a blazing hulk doomed to the bottom of the Pacific Ocean, Lexington aviators will claim five bomb hits and nine torpedo strikes on the carrier, while Yorktown fliers will claim fourteen bomb hits and ten torpedo strikes (whatever the actual count was, it is a massive overkill, and a major mistake that only 21-year-old Ensign Thomas W. Brown of the Yorktown shifts to a more suitable target, the Japanese cruiser Sazanami, before Shoho sinks), and 29-year-old Lt. JG Walter Albert Haas will be the first American pilot to be credited for shooting down a Japanese Zero with a Grumman F4F Wildcat fighter plane (for the war, American carrier pilots will claim 1,327 enemy aircraft destroyed by Wildcats against the loss of 178 F4Fs in 14,027 combat sorties).

Shoho On Fire

Over in a matter of minutes (Burch will claim that the Shoho only lasts seven minutes after being hit for the first time), running full speed as she belches plumes of black smoke from her many wounds, at a cost of only three dive bombers (two from Lexington and one from the Yorktown), Fletcher's and Fitch's pilots sink the first Japanese carrier of WWII, costing the Japanese the carrier, her compliment of 21 combat aircraft, and 638 sailors and airmen (later in the day,.the Japanese destroyer Sazanami will pluck 203 men from the water, with one being Shoho's captain, Ishinosuke Izawa) The submarine tender turned light aircraft carrier, commissioned 11/30/1941, sinks Thursday, at 11:35 in the morning of May 7, 1942. High above the Shoho's watery grave, the last American flier to leave the area is 38-year-old future rear admiral Lt. Commander Robert Ellington Dixon of the Lexington, who sends a prearranged success message back to fleet. Joining a handful of previous famous moments for the United States Navy like Captain John Paul Jones pronouncing "I have not yet begun to fight," a mortally wounded Captain James Lawrence proclaiming "Don't give up the ship," Oliver Hazard Perry sending the dispatch "We have met the enemy and they are ours" from the Battle of Lake Erie, Admiral David Glasgow Farragut's attack order at the Mobile Bay "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead," Commodore George Dewey's Manila Bay order "You may fire when ready, Gridley," and Lt. Howell Maurice Forgy encouragement to the crew of the heavy cruiser USS New Orleans at Pearl Harbor to "Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition," the fleet electrifying signal from Dixon reads, "Scratch one flattop! Dixon to carrier, Scratch one flattop!" Message received and verified (before the war is over, thirteen more Japanese carriers will go the the bottom of the Pacific Ocean) when Lt. Commander Joe Taylor, leading the Yorktown's torpedo squadron lands and has the pictures developed of the Shoho sinking and takes them to Fletcher and the carrier's captain and future vice admiral, 52-year-old Elliott Buckmaster are elated. Briefly, the two men hug each other and jump up and down in the flag bridge, celebrating as if a last second touchdown pass had just won a football game for the Navy. And to some extent it has though the two men are not aware of it at the time; monitoring the situation from his headquarters at Rabaul, worried that the Americans will next pounce upon the invasion transports Shoho was screening, Admiral Inoue orders the invasion force to withdraw to the north until the Japanese can regain the initiative, which they never do.

Before She Was A Carrier

Headed To The Bottom As Shoho

Dixon

The celebration doesn't last long however as the Americans realize that the battle has not yet been won and that there are two Japanese carriers and their consorts that are still unaccounted for and the American task force could itself be attacked at any time. Deciding against sending another attack at the Japanese that might be in the area where Shoho sunk or sending his surface ships forward in a night attack, Fletcher, after recovering his raiders, moves his task force to the south to await further developments. At 5:47 p.m., the Yorktown's radar picks up a number of bogeys approaching the task force, as expected, the Japanese have arrived, but are unaware of the presence of the American carriers (the attack force of 27 planes has been personally selected and sent off by Hara to attack Crace's cruisers, thought to be battleships, in the Jomard Passage). Upping their combat air patrol to thirty planes, the Americans vector their protection towards the Japanese aerial force. Not expecting carrier-based fighters to be a problem, the Japanese force is horribly surprised when Wildcats drop down on them from 5,000 feet. Chaos and carnage result with eight Japanese planes shot down (seven torpedo planes and a dive bomber, along with damaging a second dive bomber that it crashes while fleeing to the north) and the rest scattering for safety ... but there is none to be had (three Wildcats will be lost in the dogfighting). As darkness falls, running lights on, a group of Japanese raiders begin signaling they are ready to land on their carriers, but there is a huge problem with that proposition ... in the oncoming darkness and low-hanging clouds the Japanese have become lost and try to land on the Lexington and Yorktown. The Night sky suddenly lit up by anti-aircraft fire from the carriers, their consorts, and American pilots landing, the Japanese scatter again, with eighteen damaged planes managing to make the 120 miles northeast, back to Takagi's warships (immeasurably helped by Takagi turning the searchlights on for recovery of his raiders in the darkness).

Dauntless

Wildcats On Patrol

May7th just a warm-up to what is coming, before dawn of the next day, hunting for each other, both carrier forces send search planes out to the north, south, east and west, with Lt. Junior Grade Joseph Smith in a Dauntless from the Yorktown being the first to sight Takagi's carriers. With confirmation of the sighting 200 miles to the northwest (once more Lt. Commander Dixon is in the thick of things with his verification that the Japanese carriers have been found), Fitch puts an attack force in the air of seventy-five fighters, dive bombers, and torpedo planes (the Yorktown complement consists of six fighters, 24 dive bombers, and nine torpedo planes, while the Lexington contribution to the attack is nine fighters, 15 dive bombers, and 12 torpedo planes). At roughly the same time (it is about 9:15 in the morning), a Japanese patrol plane sights the American task force and Hara sends a sixty-nine plane force southeast to attack (on their way to their respective targets, the two forces will pass each other in the sky). The storm clouds and overcast of the previous day now protecting the Japanese fleet, when the Yorktown pilots arrive at the scene and launch their attack (at roughly 11:00 a.m., due to the late arrival of the carrier's torpedo planes), only the Shokaku is out in the open and available to attack. Pilot inexperience, windscreen fog, launching their torpedoes from too great a distance and Japanese seamanship make the American's aim questionable, and Shokaku is only hit by three 1,000 pound bombs (American fliers will claim six bomb hits and four torpedo strikes ... all eleven of the torpedoes sent Shokaku's way by Lexington fliers miss); not enough to sink the carrier, but enough to maul her so badly (she is hit on her port bow, at the starboard side of the end of her forward flight deck, and just abaft her command island) that 51-year old Rear Admiral (he has been promoted from captain to admiral just days before on 5/1/1942) Takatsugu Jojima requests to withdraw from the area as his carrier can not launch or land planes (and it's crew has been lessened by 223 men). Request granted by Takagi and Hara, at 12:10 in the afternoon, the crippled Shokaku begins it's long journey back to Japan, a voyage during which the carrier almost sinks returning to the Japanese naval base at Kure. Fixing her ills, the ship will be out of commission until July 14, 1942.

Shokaku Under Attack

Shokaku Under Attack

Cloud cover of the previous day now gone, 150 miles to the south, the Lexington's radar picks up Hara's attack force approaching from 68 miles out and the carrier unit reacts by putting all of their available fighters into the sky (the other fighters are with the Americans bombing the Shokaku), seventeen in all, supplemented by twenty-three bombless Dauntless bombers (8 from Yorktown and 15 from Lexington). On the Lexington and Yorktown, watertight doors are secured, gasoline is purged from the ships' fuel lines, and first-aid kits and fire hoses are readied for use. Arriving overhead with less than a full attack force due to the loss of fliers on the previous day, commanding the Japanese torpedo planes, Lt. Commander Shigekazu Shimazaki sends fourteen planes after the Lexington and four after the Yorktown. Battle on, as the Japanese get into position for their run-in on the carriers (the Japanese assault force is composed of 18 fighters, 33 dive bombers, and 18 torpedo planes), a Wildcat fighter shoots one torpedo plane down and a group of SBDs added to the CAP send three more Nakajima B5N "Kate" torpedo planes into the sea, while four American planes will be shot down by Zeros. At 11:13 p.m., the Japanese begin their attacks on the two American carriers.

USS Lexington Under Attack

Though not a nimble ship, the Lexington twists and turns through her initial encounter with the Japanese (she is captained by future rear admiral and three-time recipient of the Navy Cross, 54-year-old Captain Frederick Carl Sherman) and for several minutes the carrier is unhit. During that time, the Lexington will run between torpedoes that simultaneously streak by on the carrier's port and starboard beams, and have two more torpedoes run directly underneath her without exploding, before her luck runs out at 11:20, when she is struck by two Type 91 torpedoes (diabolic little devices that have a range of 2,200 yards, can travel at a speed of 42 knots, and carry a warhead of several hundred pounds of high explosives). The first torpedo to hit the Lexington buckles the carrier's port aviation tanks, while the second ruptures the port water main, forcing the ship to shut down several boilers, reducing her speed to 24 knots. A few minutes later the Lexington gets a dose of Japanese dive bombers falling on her from an elevation of 14,000 feet, and the carrier is hit twice more, causing fires that are contained by 12:33 p.m. Though wounded (she has a seven degree list to port that is corrected with counter flooding), the Lexington is able to recover her aerial strike force by 2:30 in the afternoon when she begins to withdraw from the area. She is stricken though when sparks from unattended electric motors set off gasoline fumes near the carrier's central control station at 12:47 p.m., an explosion that kills 25 members of the ship's crew and takes out the ship's main damage control station. On fire again, another explosion takes place at 2:42 p.m. that causes even more fires to break out in the hanger and sends the carrier's heavy forward elevator a full foot above the flight deck while also destroying the ship's ventilation system. Shortly afterwards the Lexington loses power in the forward half of the ship. Still struggling to save the ship (with the help of three destroyers which have come alongside the carrier to assist), at 3:25 p.m. a third eruption knocks out the water pressure of the fire fighting hoses in the hanger and forces the evacuation of the forward machinery areas. Fires out of control, at 4:00 p.m. the unpowered carrier drifts to a halt and the crew begins to evacuate their wounded companions ... the death of the "Lady Lex" becomes official when Captain Sherman gives the order to "abandon ship" at 5:07 in the early evening (in all, 2,735 officers and men will be rescued by the task force). In her death throes, at 6:00 p.m. yet another series of heavy explosions takes place aboard the ship that blows the aft flight elevator apart and sends landed aircraft into the sea. Carrying on a tradition thousands of years old, thirty minutes later Sherman becomes the last man off the stricken, but still floating, ship. Ordered to put the carrier out of it's many miseries, between 7:15 p.m. and 7:52 p.m., the destroyer USS Phelps, captained by 39-year-old Lt. Commander Edward Louis Beck of Buffalo, New York, puts five torpedoes into the side of the carrier; a few moments after the last strike, the USS Lexington slips below the waves of the Coral Sea, 500 miles to the east of the coast of Queensland (she goes to the bottom having lost 216 men, along with 42 planes, 17 dive bombers, 13 Wildcats, 12 torpedo planes). Dropping to her rest, the carrier explodes one final time, breaking into pieces that finally come to rest at a depth of 9,000 feet (the carrier will be located on the bottom of the Coral Sea by the research vessel Petrel on March 4, 2018).

Explosion Aboard The Lexington

One Of The Lexington's Lost Planes

At The Wreck

While the Yorktown does not suffer the same fate as the Lexington, she too endures agonies on May 8th. Good fortune at first, all of the torpedo planes sent the carrier's way, miss hitting the ship. Captain Buckmaster's maneuvering is also masterful when fourteen Zuikaku dive bombers, led by Lieutenant Tamostsu Ema, arrive overhead. With the help of two Wildcats which disrupt Ema's attack, thirteen bombs are dodged (several of the near misses however cause damage to the Yorktown's hull below her waterline, and one is so close that it raises the stern of the carrier out of the water so much that her four brass propellers can briefly be seen churning air instead of sea), but the fourteenth bomber is able to place a single 550 pound piece of ordinance on the carrier at 11:27 in the morning, a bomb which hits the ship in the center of her flight deck, then penetrates four decks of the carrier before exploding, causing grievous structural damage to an aviation storage room, knocking out two superheater boilers, and killing or seriously wounding 66 members of the Yorktown's crew. Wounds analyzed and band-aided for the moment, repair experts aboard the carrier estimate it will take three months to make her ship shape again, and so she is withdrawn from the battle and ordered back to Pearl Harbor for repairs (withdrawing, she moves out of the area trailing a fifty-mile long oil slick). Arriving back at the Hawaiian naval base on the 27th of the month, the repair experts there ask for a minimum of two weeks to make the carrier right again. Having none of it though, Admiral Nimitz orders that the Yorktown be made ready for battle again as quickly as is humanly possible (with a window of only 72 hours for the job to get done), and with full repair crews working around the clock, in 42 hours the carrier is made battle ready once more (to get her attack capacity back up, the surviving Yorktown pilots are put ashore for R&R and replaced by USS Saratoga fliers, in Hawaii while the carrier returns to the west coast of the United States for repairs after she is torpedoed by a Japanese submarine on January 11, 1942), and when the turning-point battle of Midway begins on June 4, 1942, the Yorktown, at the cost of her own life, contributes mightily (the pilots flying off the Yorktown at the Battle of Midway will sink the carrier Soryu, locate the Carrier Hiryu, and along with Enterprise fliers, help sink the Hiryu) to the incredible victory that costs the Japanese four fleet carriers (along with a heavy cruiser) that participated in the 12/7/1941 sneak attack on Pearl Harbor.

Some Of The Yorktown's Damage

Yorktown In Drydock

The Yorktown Goes Under

Air attacks by both sides over by noon, the two strike forces return to their ships and once again cross paths, this time with several dogfights between the groups breaking out ... in one, 35-year-old dive bomber leader, Lt. Commander Kakuichi Takahashi, is shot down and killed, in another, Petty Officer First Class Kenzo Kanno, the flier that located the American task force, is taken out by a Wildcat. Forty-six of 69 planes in the Japanese strike force make it back to the Zuikaku, but upon landing, three Zeros, four dive bombers, and five torpedo planes are deemed so damaged that they are pushed off the carrier and into the sea (meanwhile, Fletcher's team loses 5 SBDs, 2 TBDs, and a Wildcat recovering his raiders); when a count is made of their aerial strength at 2:30 in the afternoon, Takagi is told by Hara that the task force now can only put 24 Zeros, 8 dive bombers, and 4 torpedo planes in the air, most piloted by inexperienced fliers. Processing the information and adding it to a belief that his team has sunk two American carriers and the lowering fuel status of his cruisers and destroyers, withdrawal from the area is requested from Vice Admiral Inoue at Rabaul, who in turn sends the request to Yamamoto. Withdrawal eventually approved, the Japanese ships head back to various bases with the MO Operation postponed until July 3rd, when another task force can be put together after an operation to take the Midway Islands from the Americans is completed ... an operation that never takes place. By the 10th of the month, both combatants have vacated the region and briefly, the Coral Sea is quiet again.

The Japanese Base At Rabaul

A decisive victory for neither side, the Japanese can claim a tactical victory by sending to the bottom more shipping tonnage than the Americans (41,286 long tons to 19,000 long tons) and by reducing by a quarter taking out the Lexington, American carrier strength in the Pacific, along with the Fletcher withdrawing from the field first. The Americans however can claim an important tactical victory ... in stopping a Japanese forward thrust for the first time in war, Fletcher has blunted the Japanese attempt to invade Port Moresby as ordered (it is also a moral victory in that the Americans prove they can go toe-to-toe with the Japanese). More importantly, the battle in which the Japanese lose ninety aircrews to thirty-five for the Americans) takes two carriers away from Yamamoto's coming Midway operation (Shokaku for damage repairs and Zuikaku for a lack of experienced fliers, exposing for the first time in the war what a problem this will soon become), making the aerial strength of both sides almost equal (233 fliers on three American carriers to 248 fliers on four Japanese carriers). Deficits becoming positives, the American Navy also uses the battle to improve its carrier tactics and equipment ... radar technology and its employment are more effectively employed, changes are made to improve communications between American ships, fliers, and land-based Allied planes, combat experience is gained that will prove invaluable in coming clashes with the IJN, fighter tactics, strike coordination between dive bombers and torpedo planes are evaluated and improved, anti-aircraft weaponry is increased and made more lethal, and damage control procedures are tweaked to improve the methods of keeping aviation fuel and its fumes from exploding during an attack.

A New Kind Of Warfare - The Yorktown From Above

As with other "great" clashes in its history, the battle is fought by men that exemplify the United States Navy's tradition of honor and bravery. Created in 1919 (and made retroactive to April 6, 1917), designed by American sculptor James Earle Fraser, the Navy Cross medal is awarded to members of the United States armed forces that while serving with the Navy, Marine Corps, or Coast Guard, distinguish themselves in combat with extraordinary heroism. It is the second highest military honor a sailor or a Marine can be awarded (following the Congressional Medal of Honor) and is the equivalent of the Army's Distinguished Service Cross, the Air and Space Force's Air Force Cross, and the Coast Guard Cross. To date, the award has been made over 6,300 times to men and now women (the first goes to Superintendent of the the United States Nurse Corps, Lenah H. Sutcliffe Higbee) in the service, with it being won the most during their careers by Marine Corps Lt. General Lewis Burwell "Chesty" Puller and Navy Rear Admiral Roy Milton Davenport, recipients of the medal five different times each (to date, five individuals have won the award four times ... WWII submarine commander Captain Slade Deville Cutter, WWII submariner Commander Samuel David Dealey, Vice Admiral Glynn Robert Donaho, Rear Admiral Eugene Bennett Fluckey, WWII submariner Commander Dudley Walker "Mush" Morton). At the Battle of the Coral Sea, the Navy Cross will be awarded 134 times, with Cross citations going to fighter, dive bomber, torpedo plane, and scout pilots, gunnery officers, commanding, executives, damage control and engineering officers, rescue boat officers-in-charge, a boat coxswain, an engineering messenger, a fuse setter, an aerial gunner observer, a medical corpsman, a senior medical officer, And there will be four Congressional Medal of Honors awarded for the battle:

*29-year-old Lieutenant William E. Hall of Utah - Flying a SBD Dauntless off the Lexington, on 5/7 Hall participates in the destruction of the Shoho. On 5/8 the pilot serves as a member of the carrier's combat air patrol, risking life and limb in a dive bomber against Zero fighters in dogfighting that sees three Japanese fighters shot into the sea and Hall being wounded.

*42-year-old USS Neosho Chief Watertender Oscar Verner Peterson, posthumously for his extraordinary courage in trying to save the furiously burning Neosho on 5/7 - Though horribly wounded himself, Peterson ignores his injuries to close four bulkhead stop valves, receiving additional third-degree burns to his face, shoulders, arms, and hands that keep scalding steam from escaping the ship's damaged engine room and enable the ship to remain operational, but also cost the chief petty officer his life a few days later.

*29-year-old Lieutenant John James Powers of New York City, flying a SBD Dauntless off the Yorktown, posthumously for three days of fighting during the battle - On the 4th at Tulagi, despite having no air cover, Powers is able to destroy a large enemy gunboat, score two near-misses that damage a large aircraft tender and a Japanese transport ship, then out of bombs, he expends the bullets in his bomber to shoot-up a second gunboat that has to beach itself on a nearby island. On the 7th, Powers leads an attack on the Shoho, finding the carrier from his Dauntless with a hit that sets off a tremendous explosion that soon sends the light carrier to the bottom. Back on the Yorktown that evening, as the ship's Squadron Gunnery Officer, the lieutenant gives a lecture to the carrier's pilots on point-of-aim anf diving techniques, emphasizing low release point bombing for better accuracy while stressing the dangers not only of enemy fire, but also the deadliness of being so low that the successful pilot might fall to his own bomb blast. On the 8th, enemy task force sited, Powers tells his squadron as they leave the Yorktown's ready room for their planes, "Remember the folks back home are counting on us. I am going to get a hit if I have to lay it on their flight deck." Making his words come to life, leading a section of dive bombers, Powers put his SBD into a dive from an elevation of 18,000 feet that takes his through bursting anti-aircraft shells and Zero fighter slugs. Lower and lower, closer and closer, far past the elevation for a safe ordinance release, at 500 feet above his target, Powers finally releases his bomb from a height where he knows it will score a hit ... and it does, striking the starboard side aft of the carrier's island where it causes fires to break out on both sides of the flight deck. Pulling up from his release point, the pilot is roughly 200 feet above Shokaku when his bomb explodes on the deck of the carrier, engulfing Powers' SBD in a cloud of flame, smoke, and debris that kills the lieutenant and his SBD.

*28-year-old Lieutenant Milton Ernest Ricketts of the Yorktown, posthumously - In charge of a damage control team, Ricketts is at his battle station when a Japanese bomb explodes in the compartment in which the sailor is standing. Mortally wounded by the blast, Powers nonetheless musters the last of his strength into opening the valve on a nearby fireplug, letting out the position's hose, and directing a heavy stream of water on the growing conflagration within the ship ... actions which help to retard the fires and save the Yorktown.

The push between powers over for the moment in the Coral Sea, the next carrier battle between Japan and America will take place in the waters and air around Midway Atoll (a 2.4 square mile spit of land roughly 1,310 miles northwest of Honolulu, Hawaii) from June 4, 1942 to June 7, 1942, and this time there will be no doubt as to the country that is victorious.

Hiryu - One Of The Four Japanese Carriers Sunk

During The Battle Of Midway