9/5/1982 - Driven home after attending a dinner honoring Marshal of the Royal Air Force, Sir Arthur "Bomber" Harris at London's Guildhall at which he will speak in praise of the commander, Sir Douglas Robert Steuart "Dogsbody" Bader suffers a fatal heart attack while passing through Chiswick, West London and dies at the age of 72.

Bader

A legendary modern English warrior, Bader is born on February 21, 1910 in St. John's Wood, London, to Major Frederick Roberts Bader, a civil engineer, and his wife, Jessie Scott MacKenzie. His first two years of life are spent living in the Isle of Mann while his father, mother, and oldest brother, Frederick (he is known as "Derick" to distinguish the two), return to India, and Frederick Sr.'s work. In 1912, the family is back together in India, but only for a year ... in 1913, Frederick Sr. resigns his post and the Baders return to London, settling in the city's Kew region, home just in time to leave again in 1914 to fight in WWI as a member of the Corps of Royal Engineers. Serving in Europe, he is severely wounded by shrapnel to his head in 1917, a wound that keeps him in France after the war ends, and kills him at the age of 55 in a Saint-Omer hospital on May 6, 1922. Shortly after her husband's death, his mother marries again, making Reverend Ernest William Hobbs her new partner in life, a life that once more Douglas does not share much of as the lad is brought up in the village rectory of Sprotbrough, at his grandparents home (where his mother often sends him when she doesn't want to deal with parenting the boy), and later as a boarder at the Temple Grove School, a prep school with a reputation for giving it's students a "Spartan" education (during this period, he shots a woman through an open window with a pellet gun as the female is about to take a bath, an incident that gets the youngster shot in turn in the shoulder at point-blank by his older brother as a lesson to demonstrate the hurt he unthinkingly has produced). Surviving a bout of rheumatic fever that almost kills him, he finally thrives when he is sent to St. Edwards School in Oxford for his secondary education and becomes a star of the school's rugby squad (so good, that he will be asked to play in a friendly pick-up game with the professional local rugby team, the Harlequins ... at one time or another, he will also become enamored with playing cricket, hockey, boxing, pistol shooting, squash, golf, gymnastics, and though against school rules, racing cars and motor cycles, it is the racing that almost get him thrown out of school), and gains a mentor when he comes to the attention of St. Edwards' headmaster, Henry E. Kendall, who convinces Bader that his academic studies must also be a priority. Grades exemplary enough to be accepted as a cadet at Cranwell's Royal Air Force College (he becomes interested in aviation in 1923 as a 13-year-old when he is introduced to flight in an Avro 504 by RAF Flight Lieutenant Cyril Burge, a new friend when the pilot marries Bader's Aunt Hazel), Bader is told by his mother that there is no money for his schooling (unbeknownst to Bader, part of his tuition is being secretly paid by one of the school's masters) so the future pilot tests for one of six openings at the college and out of thousands that take the test, finishes with the fifth best score. Eighteen in 1928, Bader enters Cranwell's cadet flying officer training program. Almost a corpse instead of a cadet, on Bader's drive to college on a second-hand Douglas flat-twin motorcycle, the youngster swerves to avoid a stray cow in the road and takes his ride on a somersaulting flight over the road's verge and a step bank, but survives the crash and after dusting himself, eight minutes later starts his first day at Cranwell.

Father

Derick & Douglas

Avro 504

Though he struggles with his studies (his commanding officer, Air Vice-Marshal Frederick Halahan will have to remind Bader he will go nowhere if he doesn't improve on placing 19th out of 21 in his class examinations), with the youngster often breaking the school's rule that cadets be in their beds by midnight, while athletics will continue to come easily, with the young flier often besting older and bigger opponents with a combination of his athletic prowess and the depth of his sheer determination to win), in the air, Bader finds a freedom that allows him to escape the regiment and rigors of all the rules his family and teachers have saddled his youth with, and a place where he can express himself on a personal level. On September 13, 1928, Bader takes his first flight in an Avro 504 with instructor Flying Officer W. J. "Pissy" Pearson. A natural in the air, after just 11 hours and 15 minutes of flight time, Bader solos for the first time on February 19, 1929 and decides his future lies in becoming a fighter pilot. Focused on the future, at the end of his studies, Bader competes for the school's "Sword of Honour" award given annually to the outstanding student officer of the year, and comes in second to British bobsledding Bronze medalist and Irish star rugby player, Patrick Bernard Coote (Coote will be killed in April of 1941 at the age of 31 while flying as an observer in a Bristol Blenheim light bomber over Greece). June of 1930 finds Bader taking his final examinations, tests he scores high on. His final fitness reports from Cranwell call him "plucky, capable, and headstrong," with his flying abilities rated as "exceptional." On July 26, 1930, Bader is commissioned a pilot officer in the RAF and ordered to join the No. 23 Squadron stationed at Kenley, Surrey (he celebrates by cashing in his motorcycle for Austin Seven car which he drives without crashing to Kenley), just outside of London, where he soon masters the unit's aircraft ... first the Gloster Gamecock (an agile biplane with a top speed of 156 mph) and then the Bristol Bulldog (the Gamecock's replacement biplane with a top speed of 176 mph ... it is a heavier and less maneuverable aircraft), a plane with directional stability problems at low speeds (when not flying or playing various sports, the pilot also spends time chasing women on the weekends). Quickly Bader becomes a daredevil of the skies flying the two planes, often getting in trouble with his superiors for performing illegal and dangerous stunts, and breaking the squadron's rule of forbidding unauthorized aerobatics to be performed under 2,000 feet (after scoring only a 38% hit rate on his target during gunnery range practice, Bader shows off for another squadron by flying an unauthorized aerobatic show ... for which a flight commander witnessing the show states that he would court martial the reckless youth if he was a member of his flight), much to their future woe, Bader's commanders, Lt. Harry Melville Arbuthnot "Wings" Day (a decorated veteran of WWI with the Royal Marines that becomes a flier in 1924) and Captain Henry Winslow Wollett (a British ace of WWI credited with 35 aerial victories, including taking out the most balloons of any RAF pilot in the war with 11 explosions) are more lenient with the youngster) do not punish his showboating. Winners of the Hendon Air Show "pairs" event in 1929 and 1930, Bader's flying puts him on the 1931 RAF Synchronized Aerobatics Display Team with Day, and before 175,000 spectators, the two win best of that year with a 10-minute performance that the London Times will describe as "the most thrilling spectacle ever seen in exhibition flying." Celebrating his triumph, and his 21st birthday, on top of the world, Bader will trade in his car for an upgrade to a MG Roadster.

Gamecock Fighter ... L-R ... Bader, Day, And

Flight Officer Geoffrey Stephenson

Bristol Bulldog

Day & Wollett

On a frosty December 14, 1931 morning, while visiting the Reading Aero Club at the Woodley Airfield in the Borough of Wokingham with two other fliers, Britain's Bader's world changes forever, when approaching 500 hours of solo flying time, he takes a civilian pilot's taunt to heart about being more talk than show while sipping coffee and decides to demonstrate his aerobatic abilities by performing one of his specialties, a slow roll at low altitude. Knowingly breaking the rules for stunts not being performed without authorization, and for keeping aerial maneuvers above 2,000 feet in the air (he already has several reprimands on his flying record for not following the safety rule ... and has watched two other pilots die doing the same stunt that year), Bader takes up his Bulldog and horribly discovers there is a reason for the rules. Gaining the speed necessary for the stunt, the 21-year-old pilot banks steeply into a turn that is to bring him on a low run across the airfield, but the Bulldog's weight causes the plane to roll to the right and drop rapidly with it's wings vertical (one witness will say that the stunt begins at the "impossible" height of only 120 feet of Bulldog elevation, while another will place the plane's height at only 30 feet). Trying to correct and gain more air, Bader and the Bulldog almost make it, but the plane's left wingtip, cowling, and propeller hit the field's grass sending the single-seat biplane into a cartwheeling mess that eventually comes to rest in a cloud of flying dirt. Running to the wreck, pilot Percy Cruttenden is the first person to reach Bader in what remains of the Bulldog, and in a huge miracle, finds the stunt flier still alive and conscious. Using a hacksaw on the plane's crushed cockpit, Cruttenden helps Bader out of the wreckage and on to a stretcher (for the rest of his life, Bader will credit Cruttenden as being one of the people that saves him ... in Cruttenden's case by getting the injured pilot out of his wrecked plane, and then on the ride to the hospital, putting compression with his hand on a severed artery in Bader's leg). Strapped down, Bader is offered a glass of brandy, but casually ignoring what has just happened to him, true to form he states, "No, thanks very much. I don't drink." Put in an ambulance, Bader is rushed to the nearby Royal Berkshire Hospital in the town of Reading, where within a minute of his arrival he is on an operating table (Bader will remember nothing about the crash beyond the horrible noise the Bulldog makes hitting the ground).

Once Upon A Time A Cockpit -

Bader's Shoes Are At The Right

Foreground

Luckily for Bader, he happens to arrive at the hospital when one of Great Britain's best surgeons, Dr. James Leonard Joyce, is visiting. Without hesitation, Joyce takes over treating Bader, especially after the pilot's clothes are cut off and the extent of the man's injuries are established ... somehow not killed instantly on hitting the ground, Bader's right leg is almost severed by the cockpit's rudder going through his knee and his left leg is broken between the knee and ankle where the pilot seat has been violently forced forward. Beginning a series of operations on Bader's lower limbs, his right leg is amputated above the knee. Left shinbone shattered, Joyce tries to save the flier's other leg, but days after taking Bader's right limb, the left becomes infected and displays signs of gangrene setting in, and it too is amputated, this time just below the knee. Injuries, infection, blood loss, for days it looks as if Bader will perish and his family is warned more than once that the youth is on death's door, but from Christmas of 1931 his condition stabilizes (after Bader overhears a nurse discussing his upcoming death with a doctor and decides otherwise) and he begins to slowly recover from the crash as he takes copious amounts of morphine to deal with the pains from two phantom limbs. Despite everything, Bader retains his droll sense of humor, and when Joyce apologizes for not being able to save the flier's legs, he quips, "That is alright doctor. I'll get myself a pair of longer legs. I have always wanted to be somewhat taller" (describing the crash in his flight logbook, Bader will write, "Crashed slow-rolling near ground. Bad show. And when he is chastised for his lack of discipline, Bader will retort, "Rules are for the obedience of fools and guidance of wise men!"). On January 15, 1932, Bader is allowed to get out of bed for the first time, and using crutches and a walking aid for his left leg, the pilot is soon motoring about the hospital. Following months of more surgery and recuperation, in April of 1932, Bader is transferred to the RAF Hospital in Uxbridge, West London, a medical facility specializing in working with fliers that have lost limbs. At Uxbridge, the injured pilot meets Marcel Dessoutter, an airplane designer that had crashed during a test flight and lost a leg, and his brother Robert, owners of a company specializing in developing state-of-the-art protheses for amputees (light-weight from being made of aluminum). Bader is soon fitted for two of the brothers' devices, and with an excellent support team featuring fellow fliers, family, and friends, and a huge amount of guts and determination, regains a huge amount of his mobility. Normally a process that takes a minimum of six months or more to achieve, Bader shaves the process down to weeks and by the end of the year is able to walk without crutches or a cane, drive a car that has the foot petals replaced by hand operated devices on the dashboard, move about on a dance floor, and plays cricket and golf again.

Golf

His biggest achievement though is once more flying for the RAF (more than once he will tell family and friends that he would rather die than being invalided out of the organization) ... eventually. In June of 1932, Bader is able to have a personal "chat" with the Undersecretary for Air, Sir Philip Sassoon, about returning to flight service, and though at first reluctant, the minister gives in to Bader making some test flights in an AVRO 504 trainer. Successful, the pilot makes even more flights and undergoes an official examination that shows the pilot is medically fit for flying in Europe if he takes a course in aviation from the RAF's Central Flying School at Cranwell. Bader passes the course with instructors pleased by the flier's performance. He subsequently passes yet another medical examination and is convinced that he will be okayed for flight status, but is horrified when he is informed that he is not qualified for air service because there is nothing in the "King's Regulations" covering a double amputee. Later in 1932, he will be posted to the No. 19 Squadron at Duxford in Cambridgeshire and gets a job in the unit's motor transport section. Demoralized by his situation and thoroughly bored, he is officially discharged by the RAF in April of 1933, accepting a yearly pension and disability stipend of 300 pounds a month for his service. Seeking an outlet, out of the military, Bader takes a position selling petrol and other oil related products for the Asiatic Petroleum Company (presently known as Shell Oil) from a London office. He hates the work though, and continues to pepper the RAF with letters requesting his reinstatement as a flier (during this time period, while driving his mother about the countryside, the pair stop for refreshments at a tea room located in Bagshot, Surrey called The Pantiles, where Bader meets the love of his life, a waitress named Olive Thelma Elney Edwards ... in 1933, the couple marry and will be together until Thelma dies of cancer in 1971 at the age of 64). Eventually, the formidable determination that is a part of Bader's personality comes through for the flier again.

Sir Philip Sassoon

Bader Between Sister-In-Law Jill (Left) And His Wife

Thelma (Right)

1942 David Jagger Oil Painting

Of Thelma Bader

Amid the building tensions that will produce WWII in Europe beginning on September 1, 1939, Bader is secretly promised to have his status re-evaluated if war comes to Great Britain and there is a lack of experienced pilots in the RAF, and sure enough, in 1939, the pilot is invited to a selection board meeting at Adastral House in London, where Air Vice-Marshal Halahan, the commandant of RAF Cranwell during Bader's studies there, personally endorses the flier and asks that the RAF's Central Flying School in Upavon assess his capabilities. Told to report to the school for flight tests beginning on October 18th, Bader shows up at the base early and is soon undertaking aviation refresher courses to become A.1.B (full flying category status) again, and in November his persistent efforts are finally rewarded when his medical qualification is once more green lit for operational flying. On November 27, 1939, eight years after his accident, Bader flies solo again in an Avro Tutor ... and of course, being who he is, once airborne, turns the biplane upside down 600 feet above the field's circuit training area (he will quickly discover that his injuries have provided a small silver lining ... with his legs gone he no longer is prone to the blackouts of blood pooling dives and high g-force combat turns). Onward and upward, the pilot will spend time with the Avro, the Gloster Gamecock, and the Bristol Bulldog before graduating to mastering the Fairey Battle single-engine light bomber, the Miles M.9 Master two-seat advanced trainer, and finally, the RAF's main two fighter planes, the single-seat Hawker Hurricane and the single-seat Submarine Spitfire. When 1940 begins, at 29-years-old, Bader is posted to the RAF base at Duxford (near Cambridge) that is commanded by a close friend from his days at Cranwell, Squadron Leader Geoffrey Stephenson (Stephenson will be the pilot that replaces Bader in the 1932 airshow after the pilot loses his legs). Waiting for the war to turn hot (the period will be known as the "Phoney War" or "Sitzkrieg"), at Duxford, Bader practices formation flying and air tactics where he develops an attack style that favors using high altitude and dropping out of the sun to ambush enemy planes. By May, the double amputee has mastered flying his Spitfire so well that he is promoted to squadron leader ... maybe prematurely so. Leading a three-plane patrol in a morning takeoff, Bader failures to switch the propeller pitch from coarse to fine, and lacking the necessary speed for lift at 80 mph, careens through a hedgerow before cartwheeling across a ploughed field. Plane totaled, Bader suffers only a minor head wound and is back in the air later in the day, realizing that both his artificial limbs have bent by the crash forcing them beneath the rudder pedals ... an outcome that would have cost the pilot his legs if he still had them. Despite the accident, Bader is promoted to flight lieutenant and appointed the flight commander of the No. 222 Squadron of the RAF (a fighter squadron, also stationed at Duxford, that also flies Spitfires and is commanded by another Bader friend and fellow rugby player, Squadron Leader Herbert Waldemar "Tubby" Mermagen).

Mermagen

Bader Getting Into His Plane

The war hot with the German Wehrmacht's invasion of Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France, when the British Expeditionary Force is pushed back into the French port of Dunkirk and forced to evacuate continental Europe in May of 1940, the RAF is ordered to give air supremacy to men on the beaches being transported by boats back to Great Britain (Operation Dynamo that rescues 338,226 Allied soldiers from the clutches of the Germans). Part of the English efforts in the sky, flying at an elevation of 3,000 feet near Dunkirk on June 1, 1940, Bader gets into his first dogfight of the conflict and is credited with shooting down a Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter with two bursts of gunfire and damaging a twin-engine Messerschmitt Bf 110 fighter-bomber (Bader will claim five victories in the encounter). Over Dunkirk again the next day, Bader is credited with damaging a twin-engine Heinkel He 111 bomber. Three days later he almost in a crash again, this time when he almost collides with a German twin-engine Dornier Do 17 light bomber as he gets too close firing at the plane's tail gunner (he is credited with taking part on the last patrol over Dunkirk; returning to base, a weary Bader will climb into bed and sleep for almost 24 hours). His squadron by this time posted to the RAF's Kirton airfield at Lindsey (just south of the tidal estuary at Humber, on northern Great Britain's east coast), Bader is promoted to the command of the RAF's No. 242 Squadron, a group of mostly Canadian pilots that have been savaged by the German Luftwaffe in aerial combat over France (the group flies Hurricanes and is stationed at the RAF's Coltishall airfield at Norfolk in East Anglia, it's motto is "Toujours pret," French for "Always ready"). Despite initial resistance to being ordered about by a legless Englishman (the pilot will always claim he isn't legless, he is just missing the bottom of both limbs), Bader's strong personality, perseverance, and ability to cut through red tape soon has the group's morale back up and ready for a summer of dog fighting that will come to be known as The Battle of Britain. Combat ready once more, upon the formation of No. 12 Group RAF, the unit joins that command at Duxford and is declared fully operational on July 9, 1940, a day before the Battle of Britain officially begins (the group consists of 15 squadrons at 8 airfields responsible for protecting the skies over East Anglia, the Midlands, Mid Wales, and North Wales ... overall command resides with Air Vice-Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory).

Bader (Center) Admiring His Unit's New Logo Of A

Squadron Boot Kicking Hitler In The Ass

Leigh-Mallory

On July 11th, Bader scores his first victory with his new squadron, shooting down Dornier Do 17 light bomber with two bursts of machine gun fire from his Hawker Hurricane. On August 21st, under similar circumstances, he sends another Dornier into the sea near the coastal town of Great Yarmouth, then adds two more Messerschmitt Bf 110s fighter-bombers to his victory totals before the squadron is sent to Duxford and finds itself in the thick of the fighting for control of the air over England. On August 30th, the squadron claims 10 German planes, with Bader shooting down two more Bf 110s. During the month of September, on missions with his squadron repeatedly, Bader will shoot down two more Bf 110s, three Bf 109s, two twin-engine Junkers Ju 88 (and damages another), three Dornier Do 17s (and damages another), is badly shot up by a Bf 109 and has to nurse his Hurricane back to base after contemplating bailing out of his wounded fighter, and making a pass on an He 111 bomber discovers his plane has run out of ammunition, closes on the German plane to ram it before realizing what the cost might be to his group ... an ace by this point (five aerial triumphs required), September sees Bader win a Distinguished Service Order (DSO), get promoted to flight lieutenant, become a favorite subject of English newspapers, and aggressively become a proponent, along with his boss Leigh-Mallory, of the "Big Wing" concept in which RAF squadrons combine into superior numbers before engaging with the Luftwaffe. The Battle of Britain won by the end of October when Hitler cancels his cross channel invasion of England (Operation Sea Lion) and opts instead to open a new front in Russia (Operation Barbarossa), Bader receives a Distinguished Service Cross (DFC) for his services in winning the battle (the No. 242 Squadron will be credited with 62 aerial victories during the critical three months and three weeks of the clash, while only losing five fliers).

A "Big Wing" Massing Out Of Duxford

In 1941, Bader, stationed at the RAF's Tangmere airfield, is promoted to acting wing commander and becomes responsible for the activities of three squadrons of fighters (the first lessons Bader imparts is the use of a "finger-four" formation in which four aircraft fly in an inverted "V" formation with the first section leader at the tip of the formation and his wingman on the left behind him ... the second section leader flies on his right and his wingman at his right is behind him ... everyone covering for everyone else, the formation will become the standard method of operation for both the British and American air forces during the war), the 145, the 610, and the 616 (as a perk of being a wing leader, Bader is authorized to have his initials, D B, painted on his plane and his radio call sign becomes a derivative of the same two letters, "Dogsbody" ... the group's call sign is "Green Line Bus" and the pilots are soon calling themselves "Bader's Bus Company"), Squadron's converted to the newest type of Spitfire bearing two Hispano 20 mm cannons, Bader flies a specially modified cannon-less Spitfire that bears eight .303 caliber machine guns that he feels are more suited to his style of "up close and personal" combat. With the German focus turned to the east and Russia, most of the group's combat missions become escorting English light bombers over northwestern Europe and sweeps of the coastal areas to draw out the fighters of Jagdgeschwader 26, commanded by one of the Luftwaffe's best pilots, 29-year-old Oberstleutnant Adolf Josef Ferdinand Galland, already an ace with over sixty aerial victories and the future commander of the Luftwaffe's fighter force and the leader of the world's first jet fighter squadron. Dueling with Galland's command from May of 1941 to August of 1941 (from the end of March to the beginning of August, Bader will lead 62 fighter sweeps over Europe, shooting down ten Bf 109s, while claiming three probable kills and six damaged aircraft, actions for which he receives a bar for his DSO), Bader's men hold their own against the best fliers the Luftwaffe has. A change in the ace's luck though takes place on August 9th, when Bader leads a patrol of four Spitfires on a combat patrol over the French coast without his usual wingman, Sergeant Pilot Alan Smith, grounded with a head cold (on meeting the man at Tangmere, Bader will tell his protector and future ace, "Right, you'll do. Fly as my No. 2, and God help you if you let any Hun on my tail") and in London being fitted for a new uniform.

Galland In The Only Bf 109 With A Cigar Lighter

Smith

Shortly after crossing over the coast of France, Bader's patrol spots twelve German fighters below them and go on the attack. Bader's hurried descent though leaves him separated from the other fighters in his group, a problem that does not stop the ace from going after three pairs of German Bf 109s a couple miles to his front. Closing with the first pair of Germans from below and behind, Bader destroys one Messerschmitt and draws smoke from rounds he puts into the second fighter when he sees the next pair of Germans turning on him and decides to bug out of the area. In the process of leaving to fight another day, Bader's Spitfire suddenly explodes, losing portions of the fuselage behind the cockpit, along with the fighter's tail and fin. Losing height rapidly (Bader estimates he is traveling towards the ground at 400 mph from a height of 24,000 feet) as the aircraft goes into a slow spin, Bader jettisons the plane's cockpit canopy, releases his harness pin, and about to leap free of the plummeting Spitfire, is horrified to discover the foot of his right artificial leg is caught. Half in the cockpit and half out, the pilot picks just the right moment to pull the ripcord on his parachute (at 4,000 feet), and the abrupt pressure of the parachute inflating is enough to snap the retaining strap on the aluminum limb (the damaged artificial leg will later be found in an open field near the French village Blaringhem) and Bader survives the rest of his descent to the ground, all the while thinking he has been in a mid-air collision with one of the German pilots (later after the stories on both sides are compared, it will come to light that he hasn't collided with anyone or had a German shoot him down, Bader is the victim of the friendly fire of Flight Lieutenant Lionel Harwood "Buck" Casson, who fires on Bader's Spitfire thinking it is a wounded Messerschmitt ... Casson is then shot down himself and captured). Aerial combat done, the double amputee ends his dog fighting days with 22 aerial victories, four shared kills, six probable victories, one shared probable, and eleven enemy aircraft damaged ... but the war is far from over for Bader.

Casson

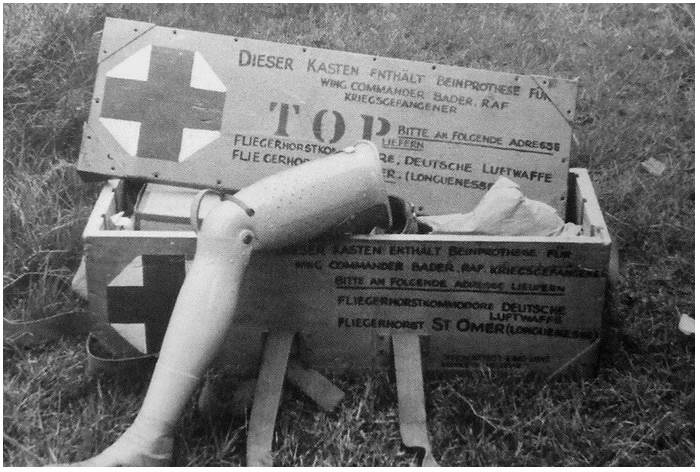

Knocked unconscious hitting the ground, Bader wakes to find himself being removed from his parachute harness by three German soldiers (he is extremely unhappy that he will have to break his date with his wife to go dancing that evening) and having his life jacket taken off. A prisoner-of-war well-known to higher echelons of the Luftwaffe, after being sent to the hospital in the town of Saint-Omer (near the site of his father's grave) for treatment of a small facial wound and a few damaged ribs, Bader soon finds himself a guest of Galland (the two men will become good friends after the war, and Bader will write the forward for Galland's tale of the rise and fall of the German Luftwaffe, "The First and The Last," and Galland will appear as a guest on the television show, "This Is Your Life," when Bader is honored by that show in 1982), with the downed pilot given a nice portion of captured British tobacco for his pipe, wine and champagne are made available (the Germans don't know that Bader doesn't drink), a formal, lavish reception of tea, other libations, and sandwiches is presented to Bader and Galland's officers by white-coated waiters, a Horch staff car tour of JG 26's airfield at Wissant is taken, and Bader even gets a chance to sit in the cockpit of Galland's Messerschmitt fighter (kidding or serious, Bader asks if he can take the plane up for a quick jaunt around the field, which Galland refuses, stating that if Bader takes off, he will be right behind him to see that the British ace can't escape back over the English Channel, words that cause Bader to clap his hands together and eagerly tell Galland, "All right, let's have a go." Galland laughs and tells Bader that he is off duty and maybe they can get into an air duel some other time (unbeknownst to Bader, the whole time he is in the cockpit, a nearby German officer is pointing a Luger pistol at his head). Impressed with his English foe, chivalry still a part of his personality, Galland will pass a request up the Luftwaffe's chain-of-command to have a replacement leg flown to France by Bader's squadron and dropped off at the German airfield without any shooting involved (at the same time, Bader's original leg is found in a muddy field and cleaned up with dings and bends repaired, is given back to Bader to use). Operation Leg approved by the Luftwaffe's leader, Reichsmarschall Hermann Wilhelm Goring, on August 19, 1941, a flight of six British Bristol Blenheim bombers, along with a large escort of fighters (making up for not being around to cover Bader's rear when he is shot down, Alan Smith will be among the pilots that ensure the group leader gets his replacement right leg) drop Bader's package (along with another artificial leg, the box also includes special stump socks, baby powder, tobacco, and chocolate bars), then they proceed on to bomb the Gosnay power station at the nearby town of Bethune (inclement weather causes the bombing part of the operation to be called off). Seeing their respect and courtesy for Bader denigrated by the failed attack (the brain child of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill), the Germans are even less amused when they discover Bader has used the artificial leg received to leave the hospital.

1941 Pencil Illustration By

Is At Front Left, Bader Behind The Gesturing Hands With

A Pipe Between His Lips

Bader's Package

Planning an escape as soon as possible once he hears his artificial leg has been found and that another is going to be dropped over the German airfield by his friends in the RAF, determined to be "a plain, bloody nuisance to the German," Bader makes contact with a local French house maid named Lucille Glaneux that works at the hospital. Lucille agrees to help Bader as much as she can ... which turns out to be quite a lot, getting a local older couple named Mr. and Mrs. Hiecques to use their house on the edge of town in the suburb of Le Haut Pont as a hideout, and arranging for a guide that can lead the airman to the Hiecques' home to be outside the hospital every night between midnight and 2:00 in the morning, smoking a cigarette (the man is a member of the French Resistance and is named Gilbert Petit). Told he is to be sent to a POW camp in Germany the next day, on the evening of August 15th, Bader puts his escape plan into effect after a German soldier locks Bader and a handful of other patients into their hospital room with his usual salutation of "Gute nacht" ("Good night"). When midnight arrives in Saint-Omer, as quickly and as quietly as he can, Bader puts his legs on and then gets into his RAF uniform. That task completed, he then lowers himself three stories and forty feet to the ground outside of the room's sole window on a rope he has crafted with his roommates made of torn up bedsheets linked together at the corners in double "granny," three hitch knots (finding the "rope" too short, recent arm amputee, comatose New Zealand pilot Bill Russell's bed is moved to the window to serve as Bader's anchor to the ground ... and when he lets go of the sheets moments later after resting on a ledge, Bader is standing on the ground). Finding his guide, Bader is led on a two mile, roughly 40 minute walk of agony through the darkened town because his "fixed" leg doesn't quite fit anymore and has rubbed his right stump bloody, and at one point Petit needs to carry the RAF pilot on his back. Arriving at the Hiecques' home, Bader is given a comfortable bed and a breakfast of bread and jam, and is assured by the couple that he is safe and will soon be home. The Germans however have another outcome in mind, and tearing up the hospital and town, a nurse remembers hearing a mention of the Hiecques, and when the Germans arrive the next day, a neighbor will relate how she heard metallic sounds coming from an out-building on the Hiecques' property the night before (she will be sentenced to 20 years behind bars by French authorities after the war). Hiding under a pile of straw in the garden, Bader is seconds away from taking a pitchfork to the ribs from the searching Germans when he pops out of his hiding place and surrenders less than 24-hours after escaping the hospital (the couple and Lucille Glaneux will go on trial for their part in the escape, despite Bader's denials that any of the trio were involved, and will be sentenced to death, a sentence that is then commuted to 20 years of hard labor in a German prison camp ... all survive the war and one day in the future, Mrs. Hiecques will appear on television at the age of 98 when Bader is honored with an episode of "This Is Your Life"). Greeted by a German sergeant speaking perfect English, "Ah, Wing Commander, we have caught you again," asking for his replacement leg, Bader is angered when instead, it, and his right and left legs are removed, and put on an overhead rack, out of Bader's reach, on the train that takes him into Germany.

Sheet Rope

The Hiecques Home

Bader's three year and eight month odyssey of captivity through a series of German POW camps begins with a stay at Dulag Luft in the town of Oberursel (the largest city in the region is Frankfurt), a reception and processing center for Allied aircrews before they are sent on to Stalag Luft camps. There, Bader, becomes an expert on "goon-baiting," the RAF art of getting under their guard's skins, which Bader achieves by singing songs without moving his mouth, acting as if he is inspecting his guards, making "raspberry" sounds during morning roll-call, having groups of men whistle show tunes to throw the guards off step when they are marching about, and giving exaggerated salutes to the enemy authorities. Soon the Germans at the camps learn to loathe Bader, which the flier's escape attempts serve to acerbate the hate they feel for "Mr. Tin Legs." Working with others on a tunnel out of Oberursel (Bader's artificial legs prove a boon to spreading tunnel dirt about the camp and for smuggling food into places the prisoners aren't allowed to eat), the RAF commander is transferred to Oflag Vlb, an officer's camp in Warburg before the tunnel is complete. At Warburg, Bader secrets letters about camp conditions out to the Red Cross, and adds another failed escape to his POW resume, getting caught by the Germans before he can even get beyond the camp's fence (as punishment, he is sentenced to ten days of solitary confinement). The failure gets him sent to Stalag Luft III on the outskirts of the town of Sagan (now a part of Poland, about 100 miles southeast of Berlin), the famous "all the bad apples in one barrel" camp where the "Great Escape" takes place in 1944. Before he can cause too many problems at Luft III, however, Bader is transferred to Stalag Luft VIII-B at the town of Lamsdorf, Poland. At the Polish camp, Bader launches his next escape attempt with Flight Lieutenant Johnny Palmer, Australian Flight Lieutenant Keith Bruce Chisholm, Sergeant Pilot Geoffrey Hickman, and Nick Carter, a Polish Jew captured in Greece that is masquerading as a British officer (vital to the plan, Carter can speak Polish, German, and English, and knows the countryside the men will be entering). With forged papers as backup, disguising themselves as regular captive soldiers in an Arbeitskommando assigned to do work on a POW camp near the town of Gleiwitz, 150 miles away, the men plan to enter the Luftwaffe training field that is nearby, steal a Messerschmitt 110 (which they have learned to fly) and make their way to freedom. The plan falls apart however when they discover there are no 110s at the airfield and the Germans discover the men are missing when an officer in the Luftwaffe comes to see Bader about conditions in the camp and is introduced to a substitute Bader that has somehow magically grown both his legs back. A new manhunt on for the pesky pilot, while Chisholm, Hickman, and Carter eventually walk their way to freedom via heading deeper into Poland, Palmer and Bader are captured.

Lamsdorf Camp

ChisholmTired of Bader's mischief, the Germans transfer the pilot to their "escape proof" flight officer POW camp Oflag IV-C, overlooking the river Zwickauer Mulde, located within the walls of Colditz Castle in the German state of Saxony (near Dresden and Leipzig), and with the grounded flier's typical dry sense of humor, he tells the authorities that he expects "to travel first class and be accompanied by a batman and officer of equal rank." At the castle, Bader finds himself within a 1,000 year old fortress with seven foot thick outer walls, that has been built on a cliff with a drop of two hundred and fifty sheer feet to the river below; a structure festooned in barbed wire with only two established exits, guarded by a large Garman garrison (the British prisoners are housed in a 90-foot tall building) that has more soldiers in it than there are prisoners in the castle. It is far from escape proof though, and over the course of the war the castle will experience over 300 escape attempts, with 36 men from a variety of countries able to vacate the place without the Germans giving their okay (one plan that never comes to fruition even involves fifty prisoners building a 240-pound, two-seat glider with a wingspan of 32 feet and a length of 19 feet and 9 inches, that is hidden in an attic for flight on a rainy night off the top of the castle's chapel to the river below ... before the glider can be tried though, WWII in Europe comes to its conclusion). Despite his history though, Bader will not be one of them ... realizing his lack of legs will be an impediment to any effort at escaping and that his celebrity while draw too much attention to any group he is discovered to be a part of, and confident the war will soon be over, Bader joins in on no more escape attempts, although he does find a new goon-baiting activity that always beings a smile to his face ... secretly dropping water balloons down on guards marching by below. Wearing a friendly, compliant mask though, during his Colditz stay, he also manages to convince the camp's commandant to allow him to take a weekly stroll outside the castle, watched over of course, by an escort of heavily armed guards. He is a free man once more on April 16, 1945, when the castle and it's prisoner of war camp are liberated by the 273rd Infantry Regiment of the 69th Infantry Division, 1st United States Army after a two day fight with SS troops.

Colditz Castle

The Glider

British Officers At Colditz - Bader Is Front Row Center

American Troops Advance Over The Colditz Bridge

War finally over for the British flier (though he doesn't know it at the time), Bader is priority processed to Paris, and then sent on London in a twin engine AVRO Anson multi-use aircraft. Arriving back in Great Britain after being gone for almost four years, Bader has a second honeymoon with his wife and is given the huge honor of leading a victory flypast of 300 planes over London in the first celebration of the British victory over the Luftwaffe that takes place on Battle of Britain Day, September 15, 1945. Posted back to Tangmere, working under base commander RAF Air Marshal Richard Alcherley (a Schneider Trophy winner of an annual seaplane race and a Bader associate from their days with No. 23 Squadron at Kenley in 1930), the pilot is put in charge of the base's Fighter Leader's School and promoted from temporary wing commander to temporary group captain. It is during this time period when he returns the kindnesses of Galland, hosting the Luftwaffe commander, fighter pilot Gunther Rall, an ace credited with 275 aerial victories in 621, the third most of all-time, and master flier, Hans-Ulrich Rudel, the only recipient of the Knight's Cross with Golden Oak Leaves, Swords, and Diamonds for flying 2,530 ground-attack in a Junkers Ju 87 "Stuka" dive bomber on the war's Eastern Front in which he destroys 519 tanks, a battleship, a cruiser, 70 landing craft, 150 artillery emplacements, nine planes, and an assortment of more than 800 vehicles, when as POWs, the threesome are processed through Tangmere where Bader wines and dines the men, gives them a tour of the English facility, and personally oversees Rudel, a fellow amputee, getting a new artificial leg from the Dessoutter Brothers. But Bader isn't that interested in overseeing classes on cooperating with ground units or dealing with squadron leaders that consider him "over the hill," or giving tours for other Luftwaffe fighter pilots, and he requests a combat assignment to fly more missions over Europe or a transfer to the Pacific to fly against the Japanese. Not to be, Air Marshal James Robb offers him the command of the North Weald sector of the RAF No. 11 Group, an organization deeply steeped in its history of battling the Germans during the Battle of Britain, but Bader turns the assignment down and on July 21, 1946 he retires from the RAF with the rank of group captain.

1945 - Back In England With His Wife And Golden

Retriever Shaun

Bader In The Blue Polk-A-Dot

Scarf He Wears For The

Away from his personal feelings about the book, movie, and author, Bader continues to fly, golf (he will manage to lower his handicap to four), go to aviation gatherings, and when the opportunity presents itself, he works with the disabled (he loves to end tales of the trauma he suffered as 23-year-old by stating, "A disabled person who fights back is not disabled, but is inspired" ... and for years he quietly visits children missing limbs and gives them hope for the future showing off his "tin legs") ... unselfish work that is noticed, appreciated, and results in Queen Elizabeth II knighting him for it in June of 1976 (she will quip that Bader is the first time she has knighted someone that was standing up) in a ceremony in which actor John Mills and Air Vice-Marshal Neil Cameron also are invested. Sadly, Thelma develops throat cancer and after a four year fight with the disease, perishes at the couple's home in London on January 24, 1971 at the age of 64. Lucky once more, in January of 1973, Bader finds love one last time, marrying Joan Murray Hipkiss (the daughter of a steel tycoon with a love of riding and a member of the British Limbless Ex-Servicemen's Association ... she meets Bader at a 1960 event of the association). From 1972 to 1978, he is a member of great Britain's Civil Aviation Authority and chairs a committee examining the effects of flying time on pilot fatigue. In 1977, Bader will be made a fellow in the Royal Aeronautical Society and also receives a Doctorate of Science from Queen's University in Belfast. By this time he has also written a book, his take on the Battle of Britain, called "Fight for the Sky: The Story of the Spitfire and Hurricane" and is serving as consultant to Aircraft Equipment International of Ascot, Berkshire. Health finally beginning to fail, on June 4, 1979, Bader flies for the last time, taking his Beech 95 Travelair (a retirement gift from Shell Oil) up over the English countryside. On September 5, 1982, Bader makes a speech at a Guildhall dinner honoring legendary Marshal of the Royal Air Force, Sir Arthur "Bomber" Travers Harris on his 90th birthday. Being driven back to his London home after his speech, Bader suffers a massive heart attack while passing through the West London suburb of Chiswick and dies at 72 (his second wife, Lady Joan Bader will pass away peacefully in her sleep in 2015 at the age of 97). Not surprisingly, when Adolf Galland hears of his friend of 42 years death while on a business trip in California, he drops his plans and flies back to England to attend the memorial service at the St. Clement Danes Church in the Strand, London.

Rudel Being Welcomed Back To Base

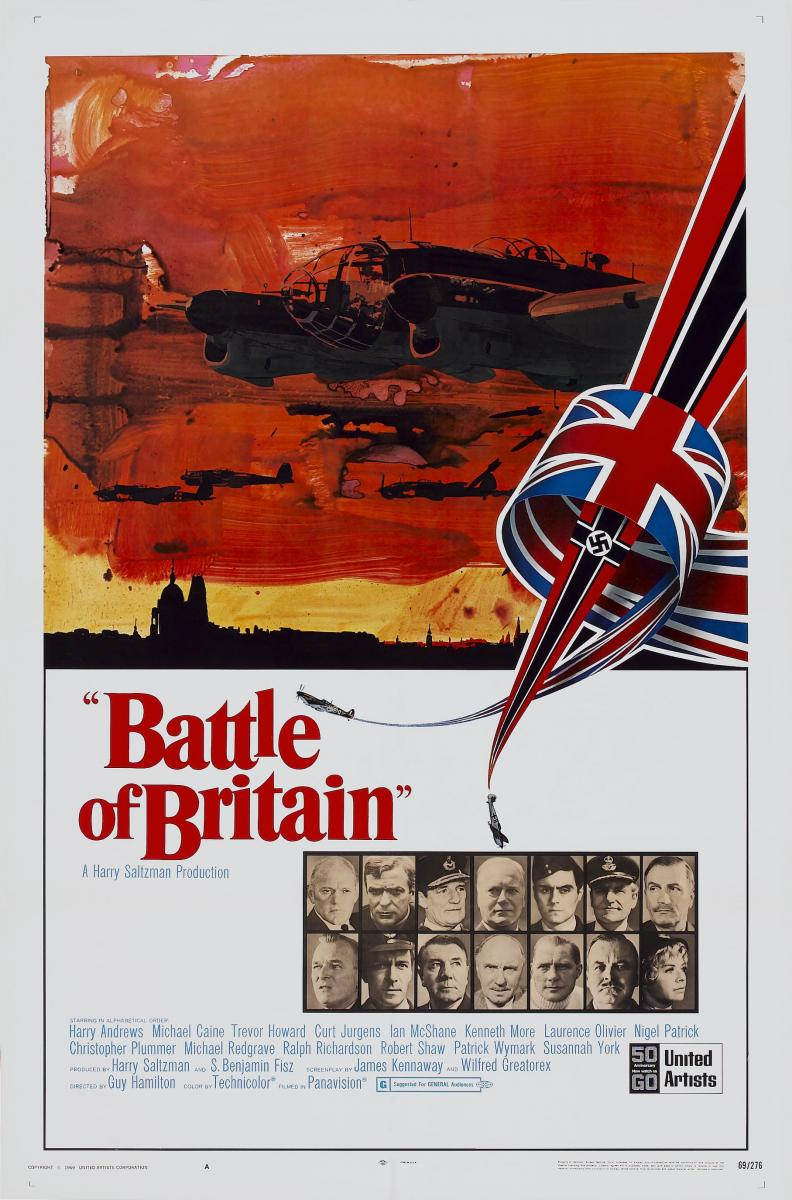

The RAF and the war behind him, Bader will continue lead a full life for the next thirty-six years. After deciding he isn't interested in running for Parliament, paying back the corporation that took care of him after he lost his legs in 1931, Bader rejoins Royal Dutch Shell, though other companies offer him more money to join their ranks, and because there is a giant perk that comes with his decision, Bader will be able to travel extensively, flying a variety of Shell aircraft (most of the time in a Percival Proctor and later in Miles M.65 Gemini or a Beechcraft Bonanza ... eventually he will log 5,774 hours and 25 minutes of flying time visiting Shell sites in Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and the United States) from destination to destination, often accompanied by a dynamic outspoken Shell vice president that becomes a dear friend, legendary retired Congressional Medal of Honor flier, General James Harold "Jimmy" Doolittle. Mixing business with pleasure, the freedom of flying also allows Bader to stay in touch with former air friends and flying foes at reunions around the world, events that allow him to renew his friendship with Galland (he will write the forward for Galland's 1954 autobiography and best seller on the history of the Luftwaffe, "The First and the Last," and he will also write the foreword for Rudel's biography, "Stuka Pilot") and refight the Battle of Britain over and over again (and of course he brings his distinctive personality to each event, attending a reunion of former Luftwaffe pilots in Munich that Galland has invited him to, as he walks into the gathering he is heard to exclaim, "My God, I had no idea we left so many of you bastards alive!"). Made a managing director of Shell Aircraft, he retires from the company in 1969, the same year he serves as a technical advisor on the Guy Hamilton directed epic, "The Battle of Britain," starring Michael Caine, Trevor Howard, Kenneth More, Laurence Olivier, Christopher Plummer, Edward Fox, Michael Redgrave, Ralph Richardson, and Robert Shaw. Advising completed, Bader then travels the world (except communist countries) promoting the film and becomes an in-demand, internationally renowned after-dinner speaker on aviation matters. In 1975, Bader speaks at the funeral of RAF No. 11 Group leader, Air Chief Marshal Sir Keith Rodney Park. Never a shy man, over the years Bader speaks on a myriad of topics, giving his very conservative opinions on politics, juvenile delinquency, capital punishment, apartheid, Rhodesia's defiance of the British Commonwealth, the second Arab-Israeli war, South Africa, nuclear disarmament and moves he would make if he was his country's prime minister. And sometimes, his opinion becomes overwhelming evident when he doesn't speak at all.

Already famous, Bader becomes even more so when after a year of interviews, former RAF flier and POW, author ("The Great Escape" - 1950, "The Dam Busters" - 1951), Paul Chester Jerome Brickhill releases his next book in 1954, the biography of Douglas Bader, "Reach for the Sky." The book quickly sells out it's initial print run of 300,000 copies, goes on to become the best-selling hardback in post-war Great Britain, and has the book's screen rights sold to producer Daniel M. Angel for $18,945. Another smash, the film of the same name, starring acclaimed English actor Kenneth More as Bader (the part is turned down by Richard Burton and Laurence Olivier) will go on to become the #1 movie in Great Britain for 1956, and will win the BAFTA Award for Best British Film of the same year (trying to get to know the man he will soon be playing on the silver screen, More invites Bader to play a round of golf at his club and is astonished when the artificial legged flier trounces him). There is a problem though, Bader doesn't like how the movie is produced, cutting out incidents and pilot friends (when the future director of three James Bond movies, Lewis Gilbert tells the flier the cuts had to be made to get the essentials of Bader's life into the two hour movie and that showing everything would make the film last more than three straight days, the ace replies that it isn't his problem and if the stuff isn't put back in he will refuse to advise on the production and won't serve as a cockpit double for Moore ... done deal, Gilbert goes on as he was and Bader does not actually appear anywhere in the movie version of his own life). The next to experience Bader's wrath is the author of the book the film is based on, and co-writer of the screenplay, Paul Brickhill. Impressed by Brickhill's "The Dam Busters," in 1951 Bader contacts the author to see if he is interested in telling his tale, he is, and with a handshake the men agree to split any proceeds from the book 50/50, sealing their agreement with a handshake. But as the book becomes a massive best seller, Bader realizes that after taxes he will be making very little, and demands a new agreement from Brickhill, this time in writing. Deal done, the men agree on Bader receiving a one-time payment from his company, Brickhill Publications Limited for "expenses" of $16,578.19, "expenses" that aren't taxed. Bader being Bader though, he soon decides that the new deal is also foul, and after a major argument with Brickhill, won't talk to the man on the phone or answer his letters ever again (and true to his word, he never again speaks to Brickhill, a decision that also results in Bader refusing to attend the premiere of the movie about his life, and despite his brother-in-law, John Addison composing the movie's music (he will not see his story for eleven years and watches it then only because it is on TV). Public unaware, the movie a hit, More's portrayal becomes the Bader that Great Britain believes actually exists, a man with a quiet, amiable, determined personality ... not the complex character he actually is, a hero that sometimes can morph into an abrasive monster infamous for arguing with superiors, cussing out fellow pilots when they don't meet his standards, and talking down to folks he believes are his lessors.

Book

Movie Poster

Away from his personal feelings about the book, movie, and author, Bader continues to fly, golf (he will manage to lower his handicap to four), go to aviation gatherings, and when the opportunity presents itself, he works with the disabled (he loves to end tales of the trauma he suffered as 23-year-old by stating, "A disabled person who fights back is not disabled, but is inspired" ... and for years he quietly visits children missing limbs and gives them hope for the future showing off his "tin legs") ... unselfish work that is noticed, appreciated, and results in Queen Elizabeth II knighting him for it in June of 1976 (she will quip that Bader is the first time she has knighted someone that was standing up) in a ceremony in which actor John Mills and Air Vice-Marshal Neil Cameron also are invested. Sadly, Thelma develops throat cancer and after a four year fight with the disease, perishes at the couple's home in London on January 24, 1971 at the age of 64. Lucky once more, in January of 1973, Bader finds love one last time, marrying Joan Murray Hipkiss (the daughter of a steel tycoon with a love of riding and a member of the British Limbless Ex-Servicemen's Association ... she meets Bader at a 1960 event of the association). From 1972 to 1978, he is a member of great Britain's Civil Aviation Authority and chairs a committee examining the effects of flying time on pilot fatigue. In 1977, Bader will be made a fellow in the Royal Aeronautical Society and also receives a Doctorate of Science from Queen's University in Belfast. By this time he has also written a book, his take on the Battle of Britain, called "Fight for the Sky: The Story of the Spitfire and Hurricane" and is serving as consultant to Aircraft Equipment International of Ascot, Berkshire. Health finally beginning to fail, on June 4, 1979, Bader flies for the last time, taking his Beech 95 Travelair (a retirement gift from Shell Oil) up over the English countryside. On September 5, 1982, Bader makes a speech at a Guildhall dinner honoring legendary Marshal of the Royal Air Force, Sir Arthur "Bomber" Travers Harris on his 90th birthday. Being driven back to his London home after his speech, Bader suffers a massive heart attack while passing through the West London suburb of Chiswick and dies at 72 (his second wife, Lady Joan Bader will pass away peacefully in her sleep in 2015 at the age of 97). Not surprisingly, when Adolf Galland hears of his friend of 42 years death while on a business trip in California, he drops his plans and flies back to England to attend the memorial service at the St. Clement Danes Church in the Strand, London.

With Joan At His Knighting

Galland & Bader

Aircraft wings no longer necessary for flight, at a time when Great Britain was in desperate need of heroes, Douglas Bader rose to the occasion as a member of an elite cadre of men that Sir Winston Churchill will place immortality on with his August 20, 1940 speech to the House of Commons honoring their efforts ... "The gratitude of every home in our island, in our Empire, and indeed throughout the world, except in the abodes of the guilty, goes out to the British airmen who, undaunted by odds, unwearied in their constant challenge and mortal danger, are turning th tide of the world war by their prowess and by their devotion. Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few." Not only a member of "The Few," Bader was also a one-of-a-kind flier that is still remembered decades after his passing in newspapers, magazines, books, and Internet articles, the movies, television, the works of the Douglas Bader Foundation assisting individuals with physical and mental challenges, a six foot bronze statue of the airman at Goodwood (the airfield where he once flew from when it was called RAF Westhampnett), a building named after him on the Sussex campus of Northbrook College, a Bader Way located in the town of Woodley, a Bader Road in the town of Poole, a Bader Walk in Birmingham, a street called Bader Close in Telford, a pub in Martlesham Heath, RAF Coltishall being renamed Badersfield, the Heyford Park Free School of Upper Heyford has a building named for him, there is a Bader Drive in Auckland, New Zealand near the Auckland International Airport, along with an intermediate school (7th and 8th Grade) named in his honor nearby, the film production company, Bader Media Entertainment CIC, represented by a logo of a pipe and a feather is named for the pilot, opened by Princess Diana in 1993, the Queen Mary's Hospital of London has a world renowned center for limb fitting and recovery known as the Douglas Bader Rehabilitation Unit, and in 2020, the city of Doncaster opens a new special school called Bader Academy that has a logo of a plane flying over the slogan, "Where Dreams Take Flight." It is a list of worthy memorials that continues to grow year after year.

Bader Statue

The incredibly full life of Douglas Robert Steuart Douglas comes to an end on this day in 1982, rest in peace Group Captain ... and well done!