Disaster

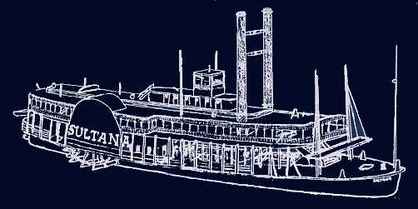

Built of wood in 1863 at the John Litherbury Boatyard in Cincinnati, Ohio to ply the cotton trade on the lower Mississippi, Sultana is one of the biggest steamers on the river, registered at 1,719 tons, the vessel has a length of 260 feet, is 42 feet at her beam, contains four decks (including its pilothouse), and is powered by four large steam boilers that turn two paddlewheels 34 feet in diameter. She is designed to have a passenger capacity of 376 and a crew of 85. Carrying supplies, and frequently Union troops, for two years the vessel is a regular on the Mississippi between St. Louis and New Orleans. Originally owned and operated by Captain Preston Lodwick, on its last voyage on the river the steamship is owned by a consortium of businessmen that includes its latest commander, 33-year-old Captain James Cass Mason of St. Louis (who is has growing debt problems brought on by his purchase of the steamship and conducting business during the war).

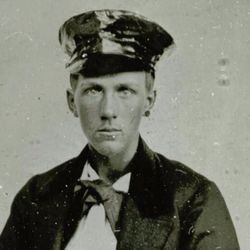

Mason

Sultana

The Sultana's last voyage begins on April 13, 1865 when she leaves St. Louis for New Orleans. Tied up in Cairo, Illinois on April 15, word reaches the city that President Abraham Lincoln has been assassinated in Washington D.C. and when Mason sets off downriver, he is carrying large stacks of Cairo newspapers to pass on the grim news. Reaching the town of Vicksburg (passage slowed by a leaky boiler), Mason makes a deal with the chief quartermaster of the town, Lt. Colonel Reuben Hatch (who gets a kickback ... a political hack, he has his job because his brother was a friend of Lincoln), to take a recently released batch of Union prisoners north for their returns home at the agreed government payout of $5 per enlisted man and $10 per officer (after they are mustered out of the army by assistant adjutant general for the Department of the Mississippi, Captain Frederic Speed) ... way above capacity, Hatch guarantees a rich haul of 1,400 former prisoners. Arriving in New Orleans, the Sultana unloads the supplies for the Crescent City and then takes on transport for the return journey north which includes 100 surplus army mules, 120 tons of sugar, 100 hogs, and 100 civilian passengers (a lucky handful get off at Vicksburg). Course reversed, the Sultana arrives back in Vicksburg on April 23 suffering now from its left hand boiler being cracked and bulging ... usually at least a three day job to repair, fearing he will lose his prisoner contract if his ship's journey is delayed, Mason (and his chief engineer, Nathan Wintringer) talks a local boilermaker repairmen, R. C. Taylor, into only doing a temporary patch job on the damaged boiler. At the same time the patch is being worked on, trains start arriving in Vicksburg with the promised former prisoners ... but with several individuals making decisions on the deposition of the men (not to divide them on to several other vessels, keeping the men grouped by the states they came from, and bad counts are made) when the Sultana leaves the port on the 24th to speed the men back to their homes, the steamship is carrying over 2,000 men on board ... 1,960 ex-prisoners (Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia veterans from the Cahaba camp near Selma, Alabama and the infamous Andersonville camp in southwest Georgia, many suffering from a variety of diseases and malnutrition), 22 guards from the 58th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, 70 paying passengers, and 85 crewmen packed into every available space, so many and so overcrowded that the vessel begins to creak and sag and has to have its decks supported by the addition of temporary heavy wooden beams.

Hatch

Cahaba

Andersonville

And the recipe for disaster is complete when the Sultana leaves Vicksburg on the 24th and immediately begins battling the Mississippi, the river in spring flood state and in some spots overflowing its banks for three miles. A last photo before its doom, at the port of Helena, Arkansas, on April 26, photographer Thomas W. Bankes, takes an exposure of the vessel that documents it epic overcrowding (and almost causes its capsizing when its occupants rush to one side of the ship to be in the shot). Memphis reached by 7:00 in the evening, the Sultana briefly offloads some supplies and then is headed north again shortly after midnight. Back on the river, the vessel takes on a new load of coal from a group of barges on the river before heading for Cairo, Illinois.

The Last Shot

More coal shoveled into the boilers to fight the steam, sometime around 2:00 in the evening, at a point where the river is about five miles wild, something goes horribly wrong below and one of Sultana's boilers blows up, followed a split-second later by two more boilers exploding. The carnage and chaos are massive and mortal (the absolute cause will never be known ... some blame the faulty patch work, others call out the boilers being made of Charcoal Hammered No. 1, a metal which tends to crack and grow brittle when subjected to repeated heating and cooling, too much pressure built up fighting the current is also postulated, the water levels, caused by the overcrowding list of the vessel, are too low in the boilers, and there is a theory that Confederate agent Robert Lowden puts a bomb (disguised as an innocent piece of coal and called a "Courtney Torpedo" after its southern inventor) in one of the boilers. Whatever sets off the explosion, the big boom sends a blast of killing steam upward at a 45-degree angle that goes through the upper decks and completely obliterates the pilothouse. Captain Mason gone in a flash, the Sultana is spun 180 degrees, catches fire, and then begins to drift down the river as her twin smokestacks topple into the water ... the left-hand one into the boiler hole below it, the right-hand one on to the crowded forward section of the upper deck. Only 76 life preservers aboard and two small life boats (hundreds killed in the initial explosion, the former soldiers of Kentucky and Tennessee that are positioned alongside the boilers are decimated), in seconds survivors have a choice of staying aboard the fire ravaged wreck, or jumping overboard to face potential drowning in the chilly flood waters of the Mississippi (the waters are full of men fighting for anything that floats ... in their weakened state from months in prison, many die of hypothermia). The next morning, after a six mile drift, one of her paddlewheels gone, the Sultana goes to the bottom of the river ... with estimates of the death toll ranging from 1,800 to over 2,100 (by contrast, 1,500 perish when the Titanic goes under after its iceberg confrontation in the Atlantic), some bodies will never be found and others will not surface for months in places as far away as Vicksburg.

Too Many People

Explosion

Disaster

For the nine hundred or so souls that somehow survive the explosion, rescue comes in a variety of ways (it is a night none of them will ever forget ... and how could they when many afterwards start participating in an annual reunion of those that escaped death ... one southern in Nashville, Tennessee, one northern in Toledo, Ohio, when the last survivors eventually pass, the reunions continue with grandchildren and great grandchildren). Boom heard and seen in Memphis and along the Mississippi's river banks, the southern town's citizens waste no time in beginning to pull people out of the water (as do the citizens of Mound City, Arkansas, now the town of Marion ... one man, John Fogelman will create a makeshift raft that plucks a handful of individuals out of the waters). On its maiden voyage down the river, the Steamer Bostona (No. 2) comes on the scene at about 3:00 in the evening and starts taking survivors on board, and other vessels that also support the rescue efforts include the steamships Silver Spray, Jenny Lind, and Pocohontas, the navy ironclad USS Essex, and the gunboat USS Tyler. Brought to local hospitals within the region, only 31 more deaths will occur between April 28 and June 28.

Survivor Alonzo Vanvlack

Disaster

Big News

The Sultana

Surprisingly, especially based on the magnitude of the disaster, no one is ever held accountable for the tragedy (the last northern survivor, Private Jordan Barr of the 15th Michigan Volunteer Infantry dies in 1938 at the age of 93, and his counterpart, the last southern survivor, Private Charles M. Eldridge of the 3rd Tennessee Cavalry, passes away in 1941 at the age of 96). Speed is found guilty of overcrowding the Sultana, but his conviction is overturned by the judge advocate of the army (based on Speed not witnessing the actual loading of the soldiers on to the Sultana). The military chooses not to place charges against West Point graduate, Captain Williams, who actually places the paroled soldiers aboard the Sultana. Captain Mason is already dead, and Hatch quits the military and becomes a civilian before he can be charged. Ouch!

Tragedy

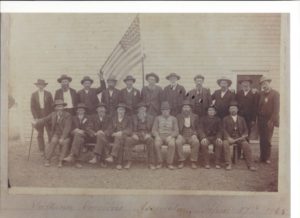

1890 Reunion

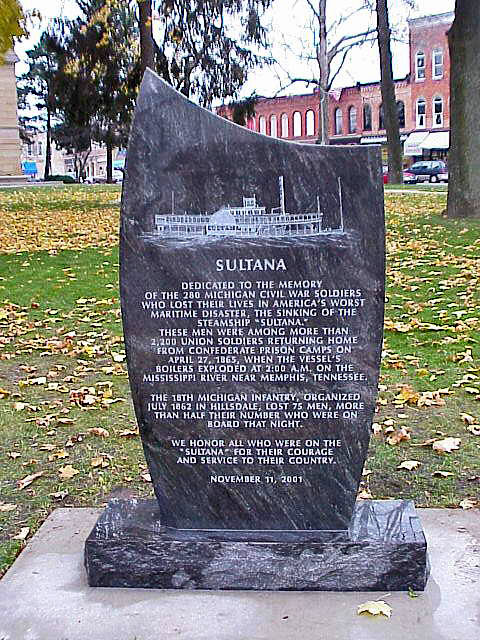

No one responsible, but not forgotten, memorials and monuments remembering the tragedy are erected in the towns of Memphis, Tennessee, Muncie, Indiana, Marion, Arkansas, Vicksburg, Mississippi, Cincinnati, Ohio, Knoxville, Tennessee, Hillsdale, Michigan, and Mansfield, Ohio. Additionally, a temporary museum, the Sultana Disaster Museum is opened to the public in Marion, Arkansas in 2015 (while funds are being gathered for a more permanent location). And in 1982, course of the Mississippi changed over the decades following the disaster (the river is two miles away from where it was in 1865), at an archaeological site established by Memphis attorney, Jerry O. Potter, about four miles from Memphis, blackened wreckage consisting of burnt deck planks and timbers is found 32 feet below an Arkansas soybean field.

Knoxville Memorial

Hillsdale Memorial

Museum Exhibit

Arkansas

Sultana